Today, the UP student finds themself entrenched in a neoliberal educational system oriented towards individualistic pursuits. It encourages the privatization of life and facilitates their withdrawal from active participation in the social processes. Self-interest is rewarded, while solidarity becomes a mere inconvenience.

These are the ideological shackles that have traditionally delimited the possibilities of collective action. They produce a breed of citizen which historian Renato Constantino has previously termed the “anti-social Filipino.”

However, times of crises have a way of jolting even the relatively comfortable out of their easy complacency, thereby challenging the presuppositions of individualist culture. Under such conditions, the prospect of non-involvement becomes less and less appealing to the idealistic young person.

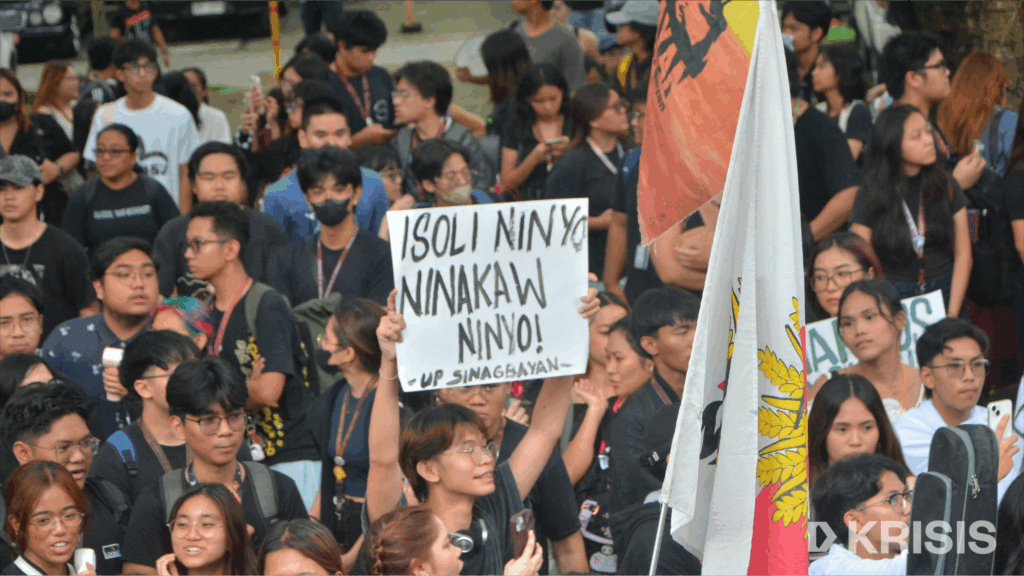

The massive turnout at Diliman’s Black Friday walkout last 12 September marks a crucial stride in the youth movement. It reflects a student body that is neither ignorant of nor apathetic to the country’s broader social ills.

A whopping attendance of about five thousand can only be made possible by the development of a counter-consciousness antagonistic to social inertia. Not only does it indicate collective rage over injustice, but so too does it signal the youth’s increasing acknowledgement of the common destiny that binds all individuals of a nation to one another, through which one could lay claim to the people’s oppression as a personal offense.

The controversy surrounding anomalous infrastructure projects involving trillions of pesos worth of taxpayer money has become a cause célèbre for the Filipino people, generating wave after wave of street protests and demonstrations that have rippled throughout the country. Diliman’s walkout was only one instance; similar student protests against corruption have errupted at UPLB, Ateneo de Manila, Bulacan State University, and others.

The youth once again appeared vitalized and kicking yesterday as the country commemorated 53 years since the declaration of Martial Law. The two major rallies at Luneta and EDSA boasted tremendous numbers, with their respective organizers each estimating attendance at 100,000. Students within and beyond Metro Manila supplied no small percentage to these impressive turnouts.

So too must the clashes that shook Mendiola and Recto until late into the evening be examined for what they disclose of many young people’s discontent. When faith in the possibility of change within an entrenched system is lost, it is reasonable to expect that some shall seek it beyond officially sanctioned means. Prior to questions of ideology and method then, such examples of political violence must be recognized as being symptomatic of deep frustration with a broken order, as well as the bullheaded unwillingness to go on with the way things are.

After all, a nation in flames produces a people that dares to play with fire.

We are three and a half years into a second Marcos Regime. The dictator’s son feigns sympathy with the people, yet in the same breath denies his family’s sins against them. Former President Duterte is detained at the Hague for Crimes Against Humanity, while Vice President Sara Duterte continues to evade attempts at accountability for misuse of state funds and other allegations. Public trust in the House and DPWH, among other government institutions, is at an all-time low.

Weeks before September 21, police and state apparatus had already begun preparations for the suppression of popular dissent. The PNP had earlier declared its intentions to enforce a no permit, no rally policy; over 50,000 police officers were deployed at protest venues.

The disproportionately brutal response of water bombs, tear gas, and bullets against citizens as young as nine years of age betrays the cavalier attitudes of those who have long held the monopoly on violence and desire so desperately to retain it.

Meanwhile, PNP and government officials including DILG Secretary Jonvic Remulla continue to deny allegations of police brutality, even as eyewitness accounts and video evidence prove otherwise.

Such obvious anxieties of the powers-that-be only lend legitimacy to arguments for the viability of change from below. If the flowering of demonstrations and various acts of defiance across the archipelago is any indication, so too are the Filipino masses coming to realize this.

The significance of holding the two rallies in Luneta and EDSA on the 53rd commemoration of Martial Law’s declaration cannot be stressed enough. As the current President’s role in government corruption is fiercely debated even amongst protest organizers, it stands to reason that to downplay his culpability is to aromatize the Marcosian legacy of corruption and impunity that lives on in today’s crop of plunderers and thieves.

The argument of not having directly experienced Martial Law’s atrocities has often been hurled against today’s young activists. Such fallacious thinking could easily be rebuffed by recognizing the continuity that exists between the tyranny of the past and the abuses of the present.

Just as we have inherited the blood-tainted legacies of dictatorship, so too do we accept the torch passed on to us by yesterday’s heroes and martyrs. Their voices are the clarion call that echoes from the annals of history, urging us from the sidelines and rousing us to action.

Ours is not a generation that has witnessed firsthand the dictatorship’s evils, but so too do we come of age in tempestuous times. Let the oppressors quiver in their boots, for today’s young have everything to gain from the fight for a just, democratic society, where the prosperity of the nation is shared by all rather than a few.