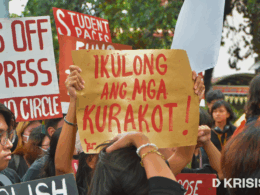

A year after the Supreme Court (SC) declared red-tagging as a “threat to life, liberty, and security,” the Quezon City Regional Trial Court (RTC) Branch 306 ruled in favor of journalist Atom Araullo’s civil lawsuit against Sonshine Media Network International hosts Lorraine Badoy and Jeffrey Celiz.

Aside from awarding him P2.07 million in damages, the court on Dec. 12 also said the former state counterinsurgency task force officials abused their right to free speech by red-tagging him.

“My primary concern, aside from the safety and well-being of my family, is also to use this case as a potential defense mechanism for journalists who experience the same kind of attacks and harassment,” Araullo said in a press conference on Dec. 19.

While the battle has been long and arduous, his landmark court win is undoubtedly a milestone in the journey towards further protecting the rights and safety of journalists.

“There is a limit to the right of free speech and in this case, the defendant abused their right,” Atty. Daphne Mendoza from the Movement Against Disinformation (MAD) said. “In a sense, the court reminds everyone to be careful of using that right for free speech.”

This serves as a precedent for both activists and journalists to file civil suits against their red-taggers, while raising questions on Badoy and Celiz’s election bid as nominees under the Epanaw Sambayanan Party-list.

But even as the 2025 midterm elections draw near, safeguards against disinformation have yet to be embedded in the electoral system.

Earlier in September, the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) released guidelines on the use of social media in digital campaigning.

Section 1, Article V of Resolution No. 11064 stipulates that any “creation and dissemination of fake news” will be subject to investigation once identified.

This coincides with Section 261(z)(11) of the Omnibus Election Code where anyone who wants to cause “confusion among the voters” by peddling “false and alarming reports or information” shall also be penalized and barred from running for public office.

“Red-tagging is disseminating disinformation and is a ground for disqualification,” MAD president Atty. Tony La Viña told KRISIS. “It’s logical to make the connection between that and red-tagging.”

While the SC has yet to decide on this, the RTC cited Araullo: “As correctly stated by the plaintiff […] ‘it (freedom of speech) is not a tool to spread defamatory statements’ or ‘to disseminate misinformation or disinformation.’”

This could put Epanaw Sambayanan at risk and open other candidates who have engaged in similar activities to further scrutiny.

In October, indigenous group Kalipunan ng Katutubong Mamamayan also called for the party-list’s disqualification due to falsely “claiming to represent indigenous communities,” stating that their continuous red-tagging has brought harm to the community.

The Republic Act 7941 or the Party-list System Act seeks to uplift underrepresented groups by giving them a seat in the House of Representatives, enabling them to draft and possibly pass laws that could contribute to the welfare of their community.

However, Epanaw Sambayanan and its nominees have had a history of targeting indigenous people in their red-tagging schemes, specifically the Lumads.

“It does not make sense that they claim to champion the marginalized and underrepresented by red-tagging certain individuals and groups just because they critically analyze the national situation and consistently call out the powers that be,” Danilo Arao, convenor of poll watchdog Kontra Daya, told KRISIS.

La Viña said the case could also be used to disqualify Epanaw Sambayanan as a whole.

The group said they are actively “studying their options” in filing for Badoy and Celiz’s disqualification on the grounds of spreading disinformation. They also added that they will take action against any candidate who dares to red-tag citizens in their campaign.

“For journalists and activists, this is a viable route,” said La Viña. “But until we find the right formula, we have to be very careful as (its regulation and implementation) can [be used] against us also.”

But even with the recent events, COMELEC has yet to make a move on Badoy and Celiz’s disqualification.

“As a quasi-judicial body, it can organize public hearings to compel these wrongdoers to attend and answer critical questions from the COMELEC commissioners (or even from election watchdogs). That it refuses to do so is an indication that it remains unwilling to confront the rich and powerful,” said Arao.

Araullo’s court win highlights the media’s confrontation with state-sponsored disinformation, including red-tagging. Awash with political clout they earned under the Duterte administration, Badoy and Celiz have declared their bid to appeal the court’s ruling.

Still, the rippling impact of Araullo’s legal victory could cascade to other red-tagging cases filed in different courts and government agencies. It could also result in reforms in criteria and guidelines with which the poll body will steer next year’s elections.