This story is part of our #CounterCheck election campaign coverage series. Produced independently in compliance with COMELEC regulations, this does not serve as an endorsement or campaign material.

If Renee Louise Co loves one thing in the world, it’s travelling.

At the height of the mass campaign against the government’s public utility vehicle (PUV) modernization program in December 2023, the 27-year-old lawyer posted on her Facebook an account of her inclination for commuting, especially during her student days. It was one act of protest against the phasing out of traditional jeepneys in line with the supposed “joint effort” of the Land Transport Franchise and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) and private entities to push for that modernization.

In her final speech for a communications subject in the University of the Philippines, she declared: “Romantic ang portrayal ko sa jeeps.”

There was that romantic sense again when Renee reshared her love affair with the act of commuting.

“Well, I enjoy travelling, but I enjoy commuting more… using public transportation—and I enjoy commuting by myself.”

Her affinity with commuting might have very well started when she was still a teenager, when her parents would wake her up early in the morning to commute, on her own, from their Malabon household to Manila Science High School (MaSci), her alma mater about 14 kilometers away from home.

Renee’s previous commuting routine back in high school revolved around a jeepney ride (or two) from Malabon to Monumento Circle and a switch to a train ride up to UN Avenue Station, near MaSci. In college, she took a different route: one bus ride to SM North EDSA from Malabon, and then one jeepney ride from SM North to UP Diliman. To move around the sprawling Diliman campus, she would take one of those famous Ikot jeepneys.

But because it is taxing to travel from one speaking engagement to another house-to-house campaign, caucus, or courtesy call to a local official in another town or province, Renee now takes on a service vehicle to ease her travel duties. However, that did not take away her love for commuting.

What could be the possible explanation behind her fascination with commuting?

“Sometimes, I just stare outside. I relish in the act of moving.”

Moving can mean a lot: mobility, transfer from one point to another, action. Moving is also a supernatural drama in Korea. For activists, moving can be synonymous to a Filipino word that has also become a unique tibak term: pagpakat.

Renee isn’t unfamiliar with the idea.

In fact, that jumpstarts a typical campaign day for Kabataan Party-list’s first nominee. “[It’s a] mix of pakat, including house-to-house or market runs, early in the morning—and another one late in the afternoon. They’re usually in different areas. In between, I will attend a speaking engagement that was arranged, or to which I was invited.”

She usually dabbles with work during the off-hours that she’s not on the campaign trail:

“Usually, I squeeze in [social media] posting. If another speaking engagement will follow, I will study the material. If there is an appearance and the talking points need to be cohesive, I will prepare my speech — or [my] talking points. Usually, also, there’s [some] debriefing… My buddy, or campaign manager, will orient us about what to expect and, therefore, what should be the proper footing for the engagement.”

Unlike most people, who play on their phones in between travelling, Renee does not do so.

If she’s gaming, she gamely shares, it’s always all in-or-nothing, kind of similar to a zero-sum game.

That might be a window into one facet of her personality, something she might be still grappling with: “I might be a one-task girlie. I try to multitask, but it might be an epic fail on my end.”

With a tag team of one staff and a driver, she managed a two-hour ride through the rush hour traffic of Quirino Avenue in Manila to arrive in time at Silvestre Lazaro Elementary School, at the heart of Brgy. Ugong in Valenzuela City. There, several young volunteers for their campaign have gathered to join her in a short visit around several Valenzuela communities to court their vote.

She had her own unique way of coping with the stress of being at the center of a national campaign. “I will not look at [this] as a de-stressing activity. This is my normal attitude with everyone I meet. When [an] opportunity arises that I can get to know someone else, I will talk with them, or I will engage them in an activity that is available to us. If anything… sleep is the only [thing] that lifts off my stress.”

That personal disposition was evident even within a day of covering her on the campaign trail.

During a leadership training seminar at the Philippine Christian University (PCU), one of her first stops for the day, Renee talked about Kabataan’s “10-point youth agenda,” their main platforms for this year’s elections, discussed the rudiments of leadership, and shared with other student leaders some of the practices and experiences from more than two decades of their political engagement and legislative struggle.

In between, she would ease in casual ways of conversation.

At various points during her PCU talk, Renee would raise a question, go around the tables of the delegates, ask someone from each table to stand up, hand the microphone over to them, and let them answer. At first, some delegates were too shy to answer; some might be too star-struck. But each one of them engaged, willingly and without hesitation.

Renee would smile at them, laugh with them at times (or crack a joke or two), raise her voice a bit when she’s emphasizing a point, or cite examples to further enrich the conversation—but she would always return to the message of alternative politics and the call for youth leadership during dire times for the country.

The young folks who sought to listen to her would often respond with sonorous applause.

Renee Co can be described in more ways than one: a diligent youth leader, an affable public figure, a firebrand in her own manner, a remarkable young lawyer. But if one wants to know the candidate Renee, beyond the persona that she presents in public, one has to hear the mundane things that can probably give a better insight into who she really is, and what she has to offer.

For example, whether or not her time to wake up from bed would be early depends upon whether or not it’s the day to wash her curly hair, because the upkeep of someone’s curly hair takes a longer time than usual.

She does her makeup on her way to an event.

She’s a soft-hearted person who can easily empathize with other people’s plight.

When she was younger, she kept a fondness for playing chess. Her father passed that hobby on to Renee and her siblings; they often played against each other, using a chess board their father bought which, in her words, had “polished wood” and all of that. It was lost in a fire. They would play as a form of family bonding, or they would play in the middle of a typhoon.

She continues: “Hoyle Games is a software that you buy and ‘download’ that is essentially a compilation of games. There are Hoyle Board Games—it has Battleships, Chinese checkers, snakes and ladders, and chess. Frequently, we boot that game when we play chess.” They would play chess only “casually”—not until Renee represented her class in an inter-school chess competition back in her MaSci days.

She won at the beginning through a casual chess play, but the pressure caught up with her, so much so that she once felt she had to consult a chess manual.

But there’s one hobby that Renee keeps to this day, a hobby that can startle someone who doesn’t know her.

The question is called Bare Necessities. There are a few common items that people keep in their pockets, or their bags—it could be your ID, wallet, keys, [or] credit card. The contents of our bags are like things that run in our minds… all of the stuff that we often have. But there are some things in our bags that make them unique.

You’re preparing for the day, you’re fixing your things. Aside from your necessities, what other thing do you want to put inside your bag? Personal organizer or address book? Hair spray or hair moose? Lucky charm? Candy or gum?

The item you wanted to bring along is something you feel a little uncomfortable being without. Your choice actually tells us something about a part of your personality you feel insecure about…

During the rush hour sojourn from Manila to Valenzuela, one of the youngest candidates for the House of Representatives chose to open a white book, read the questions aloud, and throw them around.

The book is entitled Kokology: The Game of Self-Discovery. It’s a psychological pop quiz game that Japanese psychology professor Isamu Saito and author Tadahiko Nagao slapped into a book—one that is no different from quiz books about music or New York City, or from The Carl Jung Psychology Test.

For Saito and Nagao, kokology can be defined this way: “A popular term for the interpretation of the hidden meanings of human behavior and situational responses.” Its derivation came from the Japanese word kokoro, referring to either the mind or spirit. In April 2001, frenzy went abound for their book.

The kokology craze did not spare Co—even 24 years after the first book came out, and even if she was barely four years old when the book came out. But it became a staple in her bookish quarters since she first got hold of a copy during her early college years at the University of the Philippines.

But she understands that, unlike kokology, vying for Kabataan’s renewed congressional term is not a maze of silly psychological questions. Unlike chess, it cannot be a casual endeavor. Unlike Hoyle Games, it cannot be a zero-sum race.

The hazards of continuing the uninterrupted tenure of the country’s “first, sole, and genuine youth representation” in the politico-dominated Congress might be a labyrinth effort, but it’s one path that she chose to pursue—with her family, friends, her activist background, collective, and young supporters at her beck and call.

Renee’s first political impulses started to unfold at a turbulent time.

“I grew up in the time of Gloria [Macapagal-Arroyo],” she professed, “during which your daily political diet is about how noxious corruption is in the Philippines. There was the Hello, Garci scandal, the [NBN-]ZTE scandal, her proclamation of state of emergency [in 2006].”

But while her understanding of the scandalous Arroyo administration wasn’t that extensive yet, one of the people dearest to her helped stir the pot.

“My grandmother was an avid radio listener. She’s also an avid radio commentary person,” she said with a chuckle. “We were subject to her perspectives on politics, which were actually progressive. She was a staunch critic [of Arroyo], so our political diet every morning was not only from radio, but also from her rants against the government.”

Her social awakening was rife with stories.

She tells the first one.

“My father wrote a poem during the Ethiopian famine. This was the 1980s. This was the same time as the Negros famine. He wrote a lot of poems—but on that day, we were just lying down, and then he proceeded to read the poem to me. My only visual was that piece of paper, and I was listening to him. I cried—but I wept at the end.”

She was only five or six years old at that time.

Looking back at that instance, she muses: “What happened [in Ethiopia] was horrible, it should not happen again. Like my father, I wanted to write to make others feel the same… and for all of us to agree that this should not happen again.”

She tells the second tale.

“In the early 2000s, there was a landslide in Leyte. It was documented in one Maaalala Mo Kaya episode. I remember that, while the struggle of a family that was slowly dying under the rubble was depicted, I was sobbing intermittently—to the point that my parents turned off our television, because I cannot calm down.”

Her eventual affinity with environmental struggles might have been prompted by that.

“[The story] was close to us,” Renee confided, “because Malabon is often flooded.”

She grew up in Malabon, one of the most flood-prone cities in Metro Manila. It was also the hometown of another chess enthusiast who became a towering student leader from UP’s historic past, Leandro “Lean” Alejandro. But while she did not identify herself with Lean, and while her own political awakening did not stem from Lean’s memory, her activist bent must have taken root in their lower middle class Malabon household.

In the parcel of land where Robinsons Town Malabon now exists, at the intersection of Gov. Pascual Avenue and M.H. Del Pilar Street, there used to be a string of warehouses. Her father once worked for a plywood distribution company in that area.

“The boss was his cousin-in-law. The boss kept sleeping quarters for employees, but there was also a family-size quarter [inside the compound]. He let us stay there.”

While she goes back to Malabon from time to time, “until now, we do not have a house of our own. We only rent.”

Renee’s activist “signal fire” sparked in UP.

She took up a political science course in UP Diliman’s College of Social Sciences and Philosophy. For a couple of years, her home stood inside the famous Palma Hall, which houses the historic “AS Steps.” During her freshman year, she immediately signed up for SINAG, her home college’s local student publication. She rose through the ranks, until she became its editor-in-chief.

At the height of the pandemic, when she was still a law student, she was elected to be the 38th UP Student Regent, a position that her fellow Malabon native Lean Alejandro almost had in 1984—were it not for the Marcos Sr. dictatorship.

An array of issues shaped her years, both as an Iskolar ng bayan and a UP student leader: from Rodrigo Duterte’s bloody drug war to the furtive burial of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. at the Libingan ng mga Bayani; from the fight to win free college education, cemented by the enactment of Republic Act 10931 in 2017, to a campaign to have “no student left behind” when the pandemic struck; from the unilateral abrogation of the 1989 UP-DND accord to the continuing battle to defend academic freedom—in Diliman and beyond.

Renee’s long experience with organizing work can automatically qualify her for higher forms of leadership. During her talk at the PCU forum, she asked the audience to define leadership. But how would she define it herself?

“I would define it as [the] excellent coordination and encouragement [for others] to be leaders also, to the direction that we’re all going. Leadership is duplication and replication, creating new leaders who understand why we are fighting—for our fellow youth, for the right to education.”

However, she feels that a larger challenge for youth leaders is in the pipeline. “How could we respond to the call of the times? When the most intelligent and bravest young people are summoned to come together and reverse the rotten politics of the Philippines, and build our own alternative politics.”

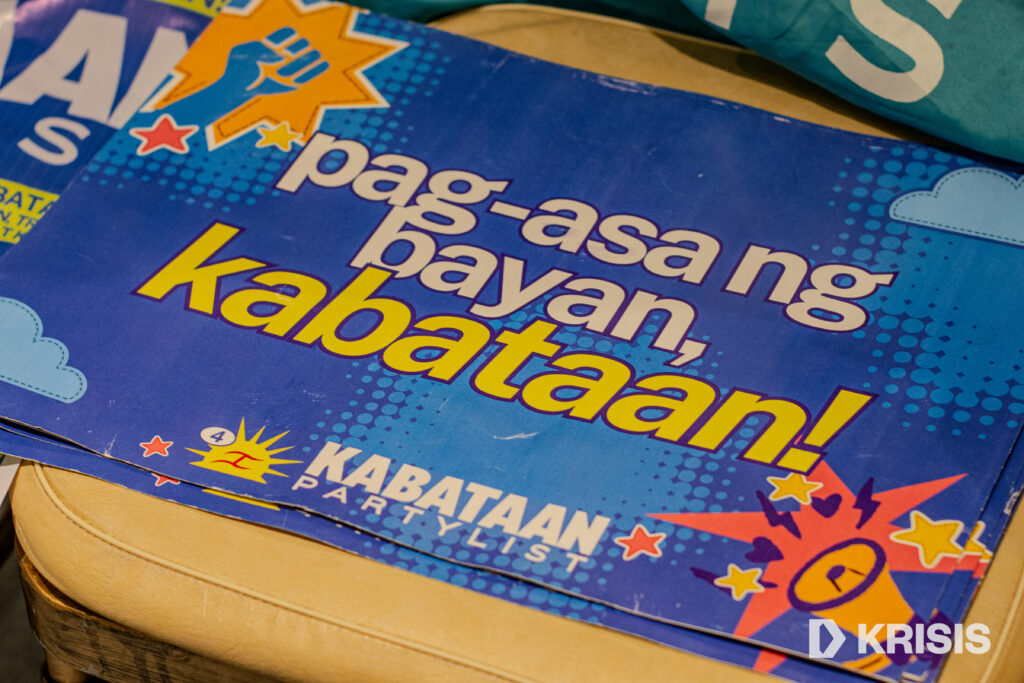

Since the establishment of Kabataan Partylist in 2001 and its first successful election in 2007, it withstood some of the biggest political crises and battles in its recent history.

Former representatives Raymond Palatino, Terry Ridon, Sarah Elago, and its current stalwart, Raoul Danniel Manuel, fought hard and innumerable struggles: To enact RA 10931, to push for pork barrel’s abolition, and to demand justice for young Filipinos slain in the Duterte drug war, among others.

Rep. Manuel also became one of the faces of the fight to expose the alleged confidential funds misuse of Vice President Sara Duterte, who now faces an impeachment trial before the Senate.

If Kabataan wins another seat on May 12, Atty. Co will be a successor to this radical tradition of youth leadership in the House. When she thinks about it, does she feel pressure? Does she feel as if she will need to fill in huge shoes?

Almost in a jest, she answered, “yes!”

But she also averred: “We’re not personalities. Kabataan Party-list is all its members, all its chapters, it is all the campaigns it is simultaneously wielding. I feel pressure that I have to perform as excellently, if not more excellently, and I think, even before I became [KPL’s] first nominee, I feel such in any responsibility, because I have a high regard for leaders and the positions they’re holding.

“But, of course, being a congressman has a different scale. But it’s also what I processed during our campaign trail: I am not alone. I will not face other congressmen alone. A whole office is helping out, and I will not wield a campaign on my own. The whole youth movement will.”

Oftentimes, during the post-Dutertismo era, when red-tagging laced with vitriol became the norm, progressive candidates are expected to meet pitchforks (metaphorically or otherwise) when they go around the country to campaign.

In Valenzuela, however, it wasn’t the case. With their members and volunteers, Kabataan Party-list’s first nominee dropped by each one of the roadside stalls in the market, campaign collaterals in hand, repeating to each person she would encounter one line that almost sounded identical: Hello, I am Atty. Renee Co, I am the first nominee of Kabataan Party-list, the first, sole, genuine youth representative in Congress…

More than once, she would point to herself in the campaign fans or leaflets they’re distributing, and tell people, with a remarkably excited tone: “Ako po itong nasa pamaypay!”

Unlike in Manila, their audience in Valenzuela was more varied: vendors, delivery riders, grandmothers, buko sellers, and some students who happened to pass them by. She had conversations with some of them, briefly asked about the education issues that they face in their schools and universities, and assured them that Kabataan will fight with them especially when it secures re-election.

Riza is a staffer from Kabataan’s national office. She joined in the house-to-house hopping that afternoon.

From her experience, the reception on the ground varies. “There are times when the atmosphere is receptive… there are times when people would talk with you, but they will literally test your knowledge about the campaigns you push for. They will play the devil’s advocate… some will ask for aid, and there are times when [people] do not want to engage at all. Those interactions were interesting. Each pakat is mixed, very colorful.”

She mentions an incident in Brgy. Pasong Tamo in Quezon City, when they met a diehard supporter of detained former president Duterte. His opening salvo: “Ayaw ko d’yan… hindi mananalo ang Kabataan Party-list.”

But after that initial attitude, Riza explained, they had a conversation about trapo politics in the country: “That’s when you will realize that the masses know the issues that are being tackled in educational discussions, the politics we’re exposing, they know it by heart.” It only takes a certain nudge.

Renee also recalled similar instances throughout the campaign. Two months ago, she and other Makabayan candidates visited Davao City, the Dutertes’ lair. Davao’s schools and students welcomed their campaign, including holding the Dutertes accountable.

“But in the communities,” she continued, “it’s a nuanced story.”

“I will introduce myself as the Kabataan Party-list [nominee]. A lot of them—maybe three-fourths—do not know about it, but when they hear about the campaign, they will say, ‘That’s right! Education should be free, wages should be higher!’ However, the remaining one-fourths already know KPL, and they know that it’s a critic of Duterte. Either they will dismiss [us] up front, or they will ask questions.”

Did she ever feel apprehensive to campaign on the ground, under an intense climate of state red-baiting?

“I don’t have any,” she proudly replied. “It’s not hard to [campaign] on the ground because […] it’s our bread and butter. It’s our flesh and bone. The reason why the organization exists is because the campaigns are continuously being refined through on-the-ground pakat.”

As the short house-to-house campaign for that afternoon in Valenzuela plodded on, neighborhood kids started to swarm Renee and the campaign team. They gamely asked for flyers to divide, stickers to post, tarpaulins to hang across their houses.

It was a sight to behold. The kids may not understand it as much yet, but policies on education and advocacies for social services that progressive leaders such as Kabataan’s nominees push will have a longstanding effect on them when they grow up, when they start entering state universities and colleges, when they start to live through the ‘evils’ of this ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial’ economy.

When the Valenzuela campaign leg wrapped up, I lit a cigarette. She then told me what happened during one of the encounters earlier that afternoon: two high school students walked up to her, introduced themselves, and asked if she was Atty. Renee.

They had a story to tell her.

Because of the recently-passed Republic Act 12006, or the Free College Entrance Examinations Act, they had an easier time applying for college. Kabataan was the principal author and sponsor of the law in Congress. They thanked her profusely, hugged her, and pledged their support for Kabataan.

A similar instance from Renee’s recollections then struck.

When LRT-1—the same train Renee used to ply as a high schooler—pushed its fare hike this year, progressive groups protested in front of one of its stations. A man suddenly walked toward her direction and snapped with a smirk, “Uy! NPA ka, ano?” Renee was on a quick defensive mode: “Ay, hindi po! Grabe ‘yan!” But he suddenly left.

Only a few minutes after that, just as when the protest action was about to end, a young person went to her and exclaimed, “Ikaw ba si Atty. Renee Co? Iboboto kita! Agree ako sa panawagan niyo!”

“That’s when I cried,” she looked back. “I have nothing to fear, because those who support [us] are far greater.”

Wistfully reflecting upon the experiences, the friendships, and all that made up the candidate that she is now, who offers herself for a bigger parliamentary battle, she vouchsafes: “My appreciation is that I am little bits of time and support everyone shared with me. I am an accumulation of everyone’s time and support for little ‘ol me.”

Beyond the headlines, the vilification, and the manifold perceptions people have of her and what she embodies, Renee is like every other ordinary person who contains multitudes. It’s hard to fit her into a box, into any catchphrase or caricature.

Her experiences molded her, her pedigree helped build her capabilities, her family and comrades shaped her perspective. If one adds all of them up, it creates a dazzling sketch that she continues to draw.

Many activist leaders have often been characterized as G&D, “grim and determined.” Renee has none of that grimness but is filled with all of that determination necessary to fight for the rights that young Filipinos are wont to enjoy and receive from the state.

She is militant, for sure, but hers takes on a different form: one that is enmeshed with youthful hope, a charming smile, and a braver heart.

In a letter he penned from his Fort Bonifacio cell in 1985, Lean Alejandro wrote: “I am sure you will agree with me when I say that the greatest adventure on earth today is our struggle for freedom. The pain and the sacrifice are staggering. The battles are historical. And the victory shall be truly glorious indeed.”

Renee Louise Co isn’t a fan of The Lord of the Rings, unlike the slain UP student leader, but she’s somehow fond of adventure. This campaign might very well be a Renee-issance of that adventurous milieu in this collective struggle, not only for rights and welfare, but for the young Filipino’s own emancipation.