This story is part of our #CounterCheck election campaign coverage series. Produced independently in compliance with COMELEC regulations, this does not serve as an endorsement or campaign material.

Marikina City is known for a number of things, among which are its famous shoe industry and the historically-significant Marikina River. It’s partially due to the latter as well as to its other geographical features, including its position in a low-lying area, that the city has also grown to be identified with its notorious flooding issues.

As no small number of Marikeños have witnessed firsthand, any significant amount of rainfall should suffice to fill the city’s road networks with up to knee-level floodwater.

En route to the Barangay Fortune PUV Terminal to meet Rene Mira’s campaign team, horror stories of flooding and closed down roads ran through my mind. It was noon, yet the sky was atypically dark and gloomy; overhead, clouds clumped ominously.

The stormy weather that had passed through Metro Manila in the previous days did nothing to soothe my worries. We were silent as we crossed over to the opposite end of Tumana Bridge, driving over the river below. I could only think about what a pain in the ass it would be to end up stranded.

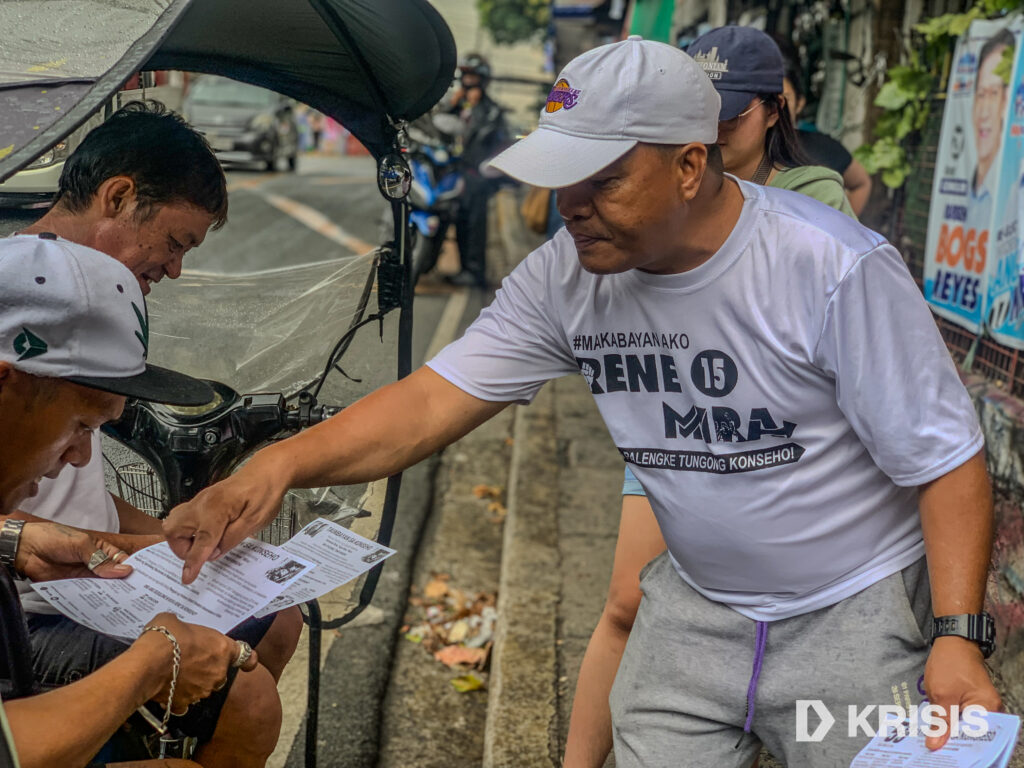

Arriving at the terminal, we quickly met up with Rene and his campaign team. With his team were about four young organizer-volunteers from across Metro Manila.

It was a small one, and they had rented a single jeepney with which they travelled from point to point throughout their campaign trail across District 2.

Rene Mira is running as a city councilor of Marikina’s second district under the Makabayan slate. With a population of about 280,000 according to a 2020 PSA report, Marikina’s second district is composed of seven barangays: Concepcion Uno, Concepcion Dos, Nangka, Parang, Marikina Heights, Tumana, and Fortune. It is in Barangay Fortune where Rene has resided since 1998, and where he currently serves as president of the Fortune United Vendors Association.

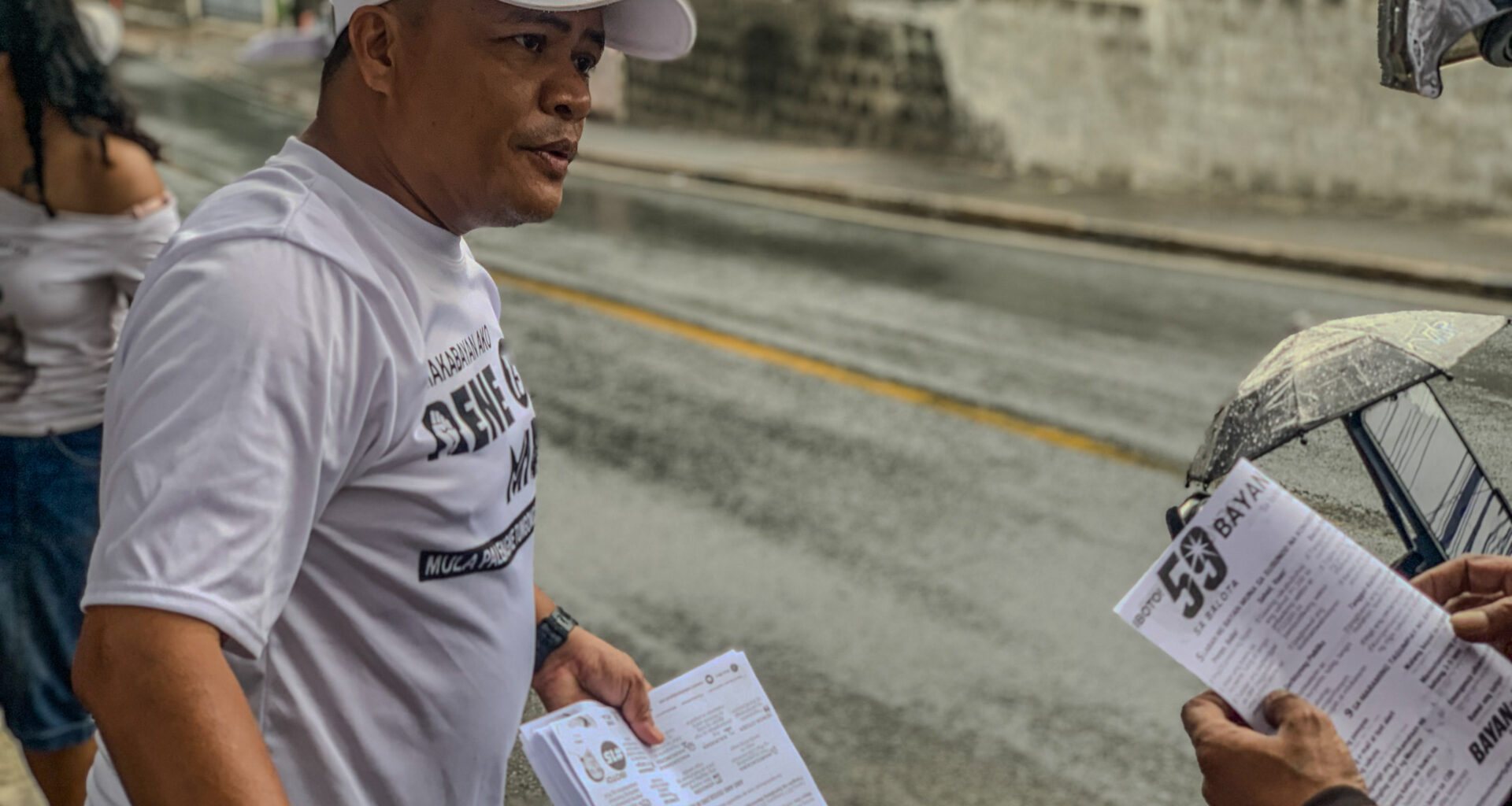

Competing for foot space on the jeepney floor were propped up a medium-sized cardboard box of flyers and a loudspeaker they had been using to blast Rene’s and other Makabayan candidates’ jingles as they made their rounds through the city.

They’d managed to purchase that very speaker for only a couple thousand pesos, and with the express intention of utilizing it for this very campaign. It seemed to him a steal, since every saved peso counted; politics has always seemed, after all, a rich man’s game.

From vendor to activist

He started organizing in 2004, when he became a member of Anglo Kilusang Mayo Uno until 2007. He then campaigned for the now-defunct Anakpawis Partylist, also under Makabayan. This was followed by a stint as president of the Samahang Manininda na Nagkakaisa sa Marikina (SAMANA), an organization he helped found.

“Mula doon sa 2004, naliwanagan ako,” he explained. “Nakita ko talaga yung kahalagahan ng pagkilos, kasi ‘yung kahalagahan n’ung pagkilos, e ‘yun talaga ‘yung magiging boses ng lansangan e.”

Like many activists young and old, Rene’s commitment to street politics had become a source of conflict within his own family. In a show of vulnerability, he confessed that although he traces his lineage to grandparents and great-grandparents who participated in the revolutionary struggle, his own parents had never approved of his political involvement.

That, however, didn’t stop him. His own experiences as a street vendor in the city played no small part in solidifying his own convictions as an activist.

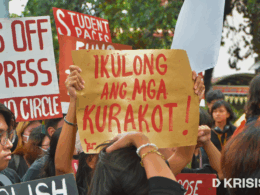

Rene recalled the pervasive harassment of vendors and confiscation of their goods by city authorities during the term of former Mayor Del de Guzman. Such harsh operations tended to be carried out with excessive brutality.

“Grabe ‘yung hulihan sa amin. Andyan ‘yung mga paninda namin, kukunin ng [clearing operation team], itatapon na lang d’un sa trak. Parang ginagawa siyang […] ‘yung parang pinapakain sa mga baboy, gan’un. Bigla-bigla lang kukunin tapos itatapon sa trak, sasagasaan ng trak ‘yung mga paninda namin.”

The continued harassment against street vendors made Rene and others recognize the importance of establishing an organization that would ensure their protection and register their calls to the upper echelons of city government. This led to the formation of SAMANA, or the Samahang Manininda na Nagkakaisa ng Marikina.

SAMANA quickly grew. Rene recalled a particular Black Friday protest in which he claims the group boasted some 800 participants. This caught the attention of then Mayor de Guzman, who invited the group for talks with the city council. The product of these dialogues was a change in the city’s Implementing Rules and Regulations [IRR] that authorized vendors to sell their goods on primary and secondary roads.

For him, this only confirmed the power of activism from below as a force for change.

In a city such as Marikina that has traditionally succumbed to the interests of political dynasties and other powerful figures, Rene insists the the people need an activist in local government. He views his candidacy, alongside those of allied candidates under the Makabayan slate, as a viable alternative to traditional, elite politics.

“Tayo yung lilinaw sa politika,” he said. “Para maiba lang. Para [magkaroon ng] transparency, para may maging boses ng mamamayan sa konseho, at talagang maisulong ang mga programang makamamamayan.”

Such pro-people programs may have unique particularities at the local level unlike the national, as they are beholden to a different set of challenges.

“Sa konsehal kasi, talagang ini-nitty-gritty mo ‘yung mga bahagi ng isang siyudad na kung saan nagla-lock pa nga ‘yung mga programs ng anumang current administration na nakaupo.,” Xyril Perez, one of Rene’s campaign staff, explained.

One such local issue Rene and his team have found to be most relevant to District 2 is the inefficiency and negligence senior citizens experience when receiving their pensions. Even after submitting all required documents to the DSWD, Xyril said many senior citizens’ requests still go unanswered without any reasonable explanation from the concerned offices. Part of his platform is the remedying of this slow and inefficient process.

Another relevant issue would be the perennial one of flooding.

Flood infrastructure in Marikina

“Magandang hapon po. Puwede pong makisilong?”

Sure enough, it did rain as we trailed Rene’s campaign team across Parang. As it fell in sporadic torrents—heavy now, lighter later—the six or so of us would quickly look for a roof or awning under which we could wait it out.

It was Rene that would ask permission from the shop and homeowners to seek a few minutes of shelter. He would make his request in a soft, polite, and almost shy voice. As we waited, he would take the opportunity to introduce himself and make small talk.

I knew the weather had been somewhat inclement those previous days that Rene’s campaign team had been making their rounds throughout District 2. Yet when asked of the experience he held most memorable during the campaign period, it was that very rain that popped up in his mind.

“Nagso-sortie kami, kasama mga flyers, basang-basa kami sa ulan tapos may mga pagkakataon talaga na gabi, tapos nag-assessment kami ng mga nangyari. So ayun, masaya na pagod {…] medyo very memorable ‘yung mga gan’ung situation. Very memorable.”

For an organizer like Rene, fickle weather could prove inconvenient—more often than not even dangerous—when running a local campaign. For the most vulnerable sectors of society, the threats of real harm are amplified.

Xyril explained the importance of local government infrastructure projects that have undergone proper consultation with communities involved and address the roots of flooding. She cited a specific case in the Police Village wherein a constructed barrier meant to mitigate its effects proved less than effective.

“‘Yung pinagawang infrastructure sa katabi ng bahay nila, hindi lapat sa gusto nila kasi ang gusto nilang mangyari, ‘pag may infrastructure na ipapatayo, iconsult muna sila… [A]ng parang barrier d’un sa creek, ano na lang siya, bakal na lang siya kompara sa concrete. So ang gusto nila mangyari, mas effective ang concrete kaysa d’un sa bakal kapag bumabaha na. Mas matagal tumaas ‘yung tubig kapag concrete ang harang.”

It is in even the small decision-making processes like these that Rene’s campaign team maintains Marikenyos be given a voice.

These supplement the Makabayan Marikina’s People’s Agenda, which Rene endorses as a candidate. It demands long-term solutions to the flooding problem: the approval of the moratorium on quarrying, mining, and real estate development on the Upper Marikina Watershed, as well as opposition to the Wawa, Kaliwa, and Laiwan Dams.

On the intersections of mass organizing and electoral campaigning

One cannot help but discern a continuum between Rene’s mass organizing and his electoral campaign.

Rene emphasized the necessity of understanding a community’s needs from a multisectoral perspective. As one who has devoted many years to organizing among vendors, a local electoral campaign more urgently demands the continued and comprehensive study of the multiple sectors that form a locality.

“Iba-ibang sektor yan. May kabataan, may manggagawa, may kababaihan, may senior citizen. Dapat ang isip mo talaga, very quick, very flexible, upang sa gan’un, mailinaw mo sa kanila talaga ‘yung mga dapat ilinaw sa sektor na ‘yun,” Rene explains. “Magpakabihasa po tayo doon sa ginagalawan nating sektor, upang gayon, hindi tayo mawala.”

It is in this way that changes in people’s perception and consciousness may be sparked. Mis- and disinformation, after all—be it regarding the real conditions of a particular sector or on traditional electoral politics—reach worrying levels during the election season.

As he went around Barangay Tumana handing out flyers during one of his sorties, a voice heckled him.

“’Yung mga ‘yan, anti-government!”

Rene approached his heckler and started talking to him.

“Dati pala siyang sundalo, so talaga pong may tunggalian na d’un,” Rene chuckled. “Sabi ko, kung may ganyan po kayong pagtingin sa ‘min, irespeto po namin ‘yun. Pero dapat po sa panahong ito, e magsuri kayo nang husto, dahil syempre, kung ang iba ay sumigaw ng taas-sahod sa manggagawa, kami ba ay mga terorista na? Or kung sinabi namin na ibaba ang presyo ng bilihin, terorista na kami, o salot na kami ng lipunan?”

Rene continued engaging the former soldier and clarified certain notions and accusations that state and military authorities have propagated against progressives. He recalled being invited to the man’s home at one point, with the latter eventually being persuaded and assuring Rene of his vote come election day. He had even handed him some flyers and a tarpaulin.

“Militar man ‘yan o pulis man ‘yan, ilinaw natin sa kanila ‘yung kahalagahan at ‘yung pagmamalasakit.”

The rain still hadn’t ceased when we parted with Rene and his team in the afternoon. He hailed us a passing tricycle and gave the driver instructions to take us back to the Fortune Terminal, where we had parked our vehicle earlier.

It was approaching three o’clock then. Rene and his team still had several stops remaining for the day’s trail; they expected to finish about 7 p.m. That seemed to me an optimistic estimate.

As our tricycle reached our destination, the rain outside gradually thinned out almost on cue. Disembarking, I looked up above. Slivers of sun shone through at the soft edges of clouds parting across Marikina sky.

It’s difficult to say what the future holds for the people of the city beyond the maelstrom of the campaign and election season. Whether or not Rene gets the opportunity to try and pursue his vision for Marikina, only time will tell.

Camila Guinoban contributed reporting to this story,

David John Alagar is currently an applicant for UP Journalism Club under Batch 24B.