We’re simply covering a filing of candidacy.

This was probably what the 30 journalists, who were part of the convoy that accompanied the wife of gubernatorial candidate of Maguindanao, thought.

The convoy included around 30 other people, most of them women. Mundane as it was supposed to be, the trip ended elsewhere. On their way to the provincial office of the Commission on Elections, about 100 gunmen ambushed them and sentenced them to a deplorable massacre.

Though Maguindanao has long been known to have a violent political climate, the massacre still strikes a repugnant chord. From those mercilessly murdered, some were tortured and some of the women were raped – actions that compound the mere fact that they were killed.

Toto Mangudadatu, the gubernatorial candidate, sent his wife and his sisters to file his certificate of candidacy, thinking that no harm can occur because Muslim beliefs dictate that women are to be respected to the absolute.

As further insurance, the Mangudadatus employed a cluster of journalists to cover the event, thinking that no harm can occur because there would be immediate backlash from the press in case of anything unfortunate to happen to such a large group of journalists.

The Mangudadatu used human shields to avoid the imminent hazards; lamentably, the murderers did not seem to comprehend what human meant.

Chronicles of deaths foretold

The martyrdom of the 30 media practitioners reflects the history of violence against journalists in the Philippines. From 1986, 128 journalists have been killed, pushing the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism to say that “Journalism is one of the most dangerous professions in the Philippines today” in Staying Alive. Add the 30 victims of the Maguindanao massacre, and it may be claimed that journalism is already the most dangerous profession in the Philippines.

After the Marcos regime, the trend on the number of journalists killed has generally been upward. The National Union of Journalists in the Philippines also reports that more journalists have been killed under the Arroyo administration than during the entirety of Marcos’ martial law rule. These truths have led many international agencies to place the Philippine journalistic climate under a microscope. The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists coined the Philippines as “the most murderous country for journalists” in May 2005.

The fact that there were 30 journalists killed in a single event gave the Philippines the dubious honor of the title “most dangerous country to practice journalism”. This is according to international media watchdog group International Federation of Journalists that reported that the country even ranked ahead of war-torn Iraq and destabilized Iran.

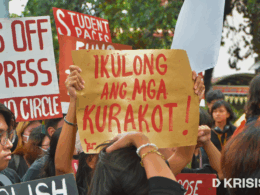

Impunity

Of the sheer number of killings of journalists, only a handful have been resolved, if any. According to the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility, “State inaction is a contributing factor to the continuing violations against press freedom.”

The most proactive response from the government to date is the establishment of Task Force Usig, tasked to prosecute cases of such violations. The slow pace of the Philippine justice system does no favors for the prosecution of such. The number of journalists being killed is increasing much faster than the number of convictions.

The nagging inaction of the government has led several journalistic agencies here and abroad to pressure the state to bring forth justice.

“The Philippines is becoming known for a culture of impunity and the government has the responsibility to demonstrate a commitment to reversing this trend,” said Freedom House Executive Director Jennifer Windsor. Since the Philippines prides itself to be a democratic state, it should exert its utmost to truly epitomize such.

Multiple choices, one answer

The Maguindanao massacre is an abhorrent embodiment of the culture of impunity relished by powerful criminals and the violent climate for journalism in the Philippines. Journalism is a proud profession and needs to continue to be such; not succumbing to the pressures and threats selfishly imposed by the power-hungry. The dubious honors the international community has given the Philippines should not serve as an indication that impunity and violence have triumphed. Instead, it should be a wake-up call to each and every one that what is occurring is, by no means at all, right.

Now, more than ever, it has been made clear to Filipinos, and even to the world, that journalism is truly under siege. Journalists are under the hazards of impunity and violence. It is said that no story is worth dying for, but at the same time, no story is worth killing for.

This article was retrieved from a Wayback Machine archive of UPJC’s old website on Feb. 7, 2010, 04:47:20 GMT.