It is cruel how something that takes decades to build, takes only minutes to crumble to dust. How does one leave a shadow looming over everything it left behind?

After a fire razed the UP Shopping Center (SC) at around 7 AM on March 8, decades-old food stalls, parlors, computer and printing shops, supplies shops and merchandise shops lost their home.

A year after, businesses are being rebuilt and 16 stalls stand upright at the temporary Shopping Center, located at the UP Tennis Court.

As the embers died, life continued on. But in its wake, the one-stop-hub for dining, printing, grooming and shopping was lost as stalls had to go their separate ways. Some tenants relocated to the tennis court, some to the Science Complex and some to Area 2.

While those at the tennis court moved only a small distance away, Grace Hermosilla, 45, and Elsa Pontod, 46, felt the gravity of this change on their profit and scales of operation.

Hermosilla, a staff of Daebak (formerly Mashitta), said that sales were less than a fourth of what they used to be. Where there used to be a steady stream of people coming in and out for Korean food, now only a few people trickle in at certain times of the day.

“Dito, sasadyain talaga ng tao, hindi katulad sa shopping na talagang matao. Walang time, walang tigil, dito after lunch wala na,” Hermosilla said.

(People have to deliberately go here [tennis court], unlike the Shopping Center which was convenient for a lot of people. Here, there are times when there are no people at all, usually after lunch.)

Currently, they are earning just enough to sustain costs for ingredients, gas and electricity. Hermosilla estimates that it will take about five years to earn back their relocation cost. Around P300,000 was spent on creating a semi-collapsible steel store structure which measures roughly 10 by 16 feet.

Stalls at the tennis court operate with limited capacities. While plans have been made, there has been no installation of permanent electrical wiring at the tennis court. Stalls in need of electricity run appliances and equipment using generators, paying for the costs out of their own pockets.

Food stall menus are limited by what food appliances their generators can sustain. Mashitta, for instance, had to stop serving ice cream. Establishments like Zagu and fruit shake stands had to relocate because it is difficult to keep ice cool and blenders running in a place with no steady supply of electricity.

Operating printers and photocopiers have also become a major challenge. In SC, all printing, binding and layouting were done on site. At the tennis court, stalls receive customer orders while mass printing happens in a different location. This forces the staff to run to and from branches, making operations more taxing and time-consuming.

On top of the extra effort needed to operate, the difference in location means that the SC permits cannot be used. In fact, stalls at the tennis court cannot use their SC stall names. This is why Mashitta is now called Daebak.

The tennis court is divided into spaces for the displaced SC vendors. The management and fee collections of all business concessionaires in the university are handled by the Business Concessionaires’ Office (BCO). It allowed tennis court stall owners to do as they wish, provided they stay in their assigned 10-by-16-feet space, refrain from digging, do not use cement and build only semi-permanent structures.

Mashita is one of the few stalls at the tennis court with a steel semi-collapsible store structure. All relocation efforts were made by SC stalls and the UP SC Stallholders Association with minimal help from offices and organizations.

Talks and negotiations with the BCO progressed slowly. For about eight months after the fire, stalls were just at the tennis court. There was little to no business operations, no income and no assurance for what was to come next. SC vendors had no one to count on but themselves.

Beyond buildings

Beyond being a hub of services, the Shopping Center was a community in and of itself. The tenants who had been there since the 1970s made the SC their home. Neighbor stalls became friends and, later, family.

It was a community that helped each other with business. Printing and photocopying operators usually referred customers to other stalls for colored printing, binding, and other services. Beyond helping customers get what they need, referrals help neighbor stalls earn and help solidify a sense of security and camaraderie among SC stalls.

It was a place of comfort, even when one was feeling sick. “Dyan kasi marami kang kausap, nakakalimutan mo yung nararamdaman mo,” Hermosilla shared.

(Back there you have a lot of people to talk to; you forget what you feel.)

She added that other stall owners treated her as a friend and an equal, not just as a staff working for the stall.

This rings true for Elsa Pontod, who owns a photocopying and merchandise store among the 16 stalls at the temporary Shopping Center.

“Parang ano na namin ‘to, second na house sa sobrang tagal na,” said Pontod who has been managing the E.B. Pontod Enterprise for 8 years now, growing from a small corner of the dressing shop of the 80-year-old seamstress, Jurozen “Sini” Asusina Serano.

(It’s really this [SC], which served as our second home. We’ve been here for so long.)

For more than two decades since she left Southern Leyte, Pontod found a home and a steady source of income from working the rounds at the Shopping Center. Over the years, she has climbed the ranks from a stall helper to an owner of her own photocopying enterprise.

The SC fire cost Pontod everything, but she hasn’t lost hope. She is willing to rebuild again, even if that means building a semi-collapsible stall in an uncovered court, withstanding the seeping heat of summer days, and buying her own generators. All of which, she said, wouldn’t have been possible without the support of the friends she’s made in her time at the SC.

Now-retired College of Arts and Letters (CAL) Professor Maria Luna, she remembers, rushed to Pontod’s side immediately after the fire was officially declared ‘out’. Offering her home as a temporary refuge and P20,000 in cash, Professor Luna’s kindness helped her business recover at a significantly faster pace.

“Kahit nung hindi pa nasunog, talagang nagbibigay yon,” said Pontod. “Kapag may mga problema kami — yung ate ko, at yung nanay ko na nasa ospital. Kapag marinig niya yan, ‘oh anong nangyari’?”, she added.

(Even before the fire, she really gives [help],” said Pontod. “If we have a problem, like my sister and when my mom was in the hospital. If she hears it, she’ll just say, ‘Oh, what happened?”, she added.)

Despite of all Pontod’s efforts to rebuild her stall, the costs of which have now exceeded P100,000, the threat of abrupt displacement from the tennis court looms over her head.

“Kaya ayon gusto ko sana may permanente na. Para kahit papaano sure ka na doon, diba?”, she said.

(What I really want is a permanent place. At least there, we are sure, aren’t we?)

The security of her old SC stall is something sorely missed. “‘Pag sinabi ni Ma’am Florendo bukas ‘oh umalis na kayo’, eh saan naman kami pupunta?” Pontod added. Dr. Raquel Florendo is the current BCO director.

(Anytime that Ma’am Florendo says we go, where else can we go?)

Today, the SC’s remnants are a painful reminder of what was lost.

“Parang ‘yung day na nasusunog, pag nakikita ko siya, nakikita mong sariwa pa talaga yun [SC fire]. Kaya sabi ko dapat gibain na yan,” Hermosilla mused.

(When I see it, I see the day when it burnt. I see it, still fresh from my memory. That’s why I say that should be demolished.)

Clearing the structure would be like wiping the pain from her memory.

Pontod, on the other hand, wants to remember. In fact, Pontod wants everyone to remember them if there should come a day that a new Shopping Center will be built.

“Kaya nga kapag may mga mag-iinterview, tanong ko, ‘Ano ba? Gagawa ba kayo ng building? ‘O sige, baka pwede naman kaming pagbigyan diyan’”, she joked, referring to students of architecture and engineering who have visited her even before the fire.

(If there are people who do interviews here, I always ask them ‘Are you going to construct a building?)

“Sana kapag [nakapagtapos] kayo, maalala niyo kami,” she added.

Just as the strength of a building depends on its foundations, the will to rebuild needs to be kindled by support from students, administrators and the UP community. The SC has nurtured the university for 45 years, now it is time to give back the help it deserves.

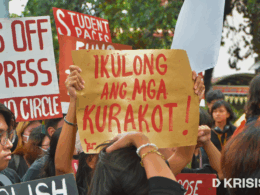

The KRISIS team has tried to get in correspondence with the Business Concessionaires Office (BCO) regarding rebuilding plans for the Shopping Center. As of writing, the BCO had not replied.

This article first appeared in KRISIS (Issue 1, AY 2018-2019) on March 9, 2019.