NANETTE CASTILLO BARED a confession.

When Rodrigo Duterte tossed his hat into the ring of the 2016 presidential elections, she almost voted for him. Like the 16 million Filipinos who voted him into office, she was enthralled by his unorthodox political appearance and rhetoric: the jokes, the grand promises, the curses.

“Magbobotohan pa lang… muntik na akong mabudol. Kasi nakita ko, uy, ibang klase ‘to, nagmumura, ang tapang,” she recalled. “Natatawa ‘ko sa mga joke niya, ‘yung mga pagmumura niya. So, noong nakita ko siyang ganoon… balak ko (na) siya iboto.”

To her surprise, the one person dearest to Nanette’s heart persuaded her against going for Duterte.

“Nung magbobotohan na talaga… tinanong ako ni Aldrin, ‘Mama, sino iboboto mo?’ ‘Duterte.’ Alam mo sagot ng anak ko? ‘Mama, ‘pag nanalo ‘yan, magiging walanghiya ang mga pulis.’”

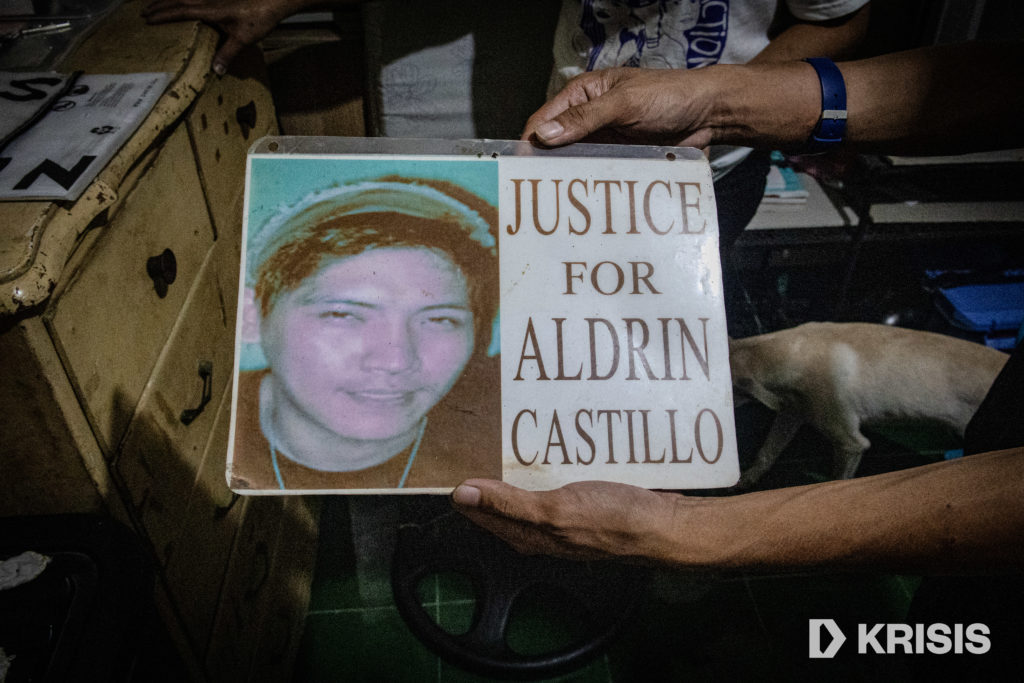

Nanette Castillo

Mother of Aldrin Castillo, one of the victims of extrajudicial killings under Rodrigo Duterte

Eight years after Duterte’s ascension to Malacañang, a sense of bewilderment and regret mixed in her tone as Nanette reconstructed her conversation with her son.

Aldrin was no activist or advocate. In fact, he was a blue-collar worker who was supposed to fly to Saudi Arabia by the end of 2017. But from a mile away, he saw what millions of Filipinos failed to sense when the notorious mayor of Davao sailed into the presidency.

“Nagulat ako. Hindi ko alam saan hinugot ng anak ko yun,” Nanette mused in retrospect.

“Dalang-dala ako ng pambubudol niya e. ‘Yung mga pagjo-joke niya, ‘yung pagmumura niya. Bentang-benta sa akin talaga ‘yun. Pero sa anak ko, hindi siya bumenta.”

The elections, however, were not the end of her dalliance with the idea of Rodrigo Duterte’s iron-fisted rule.

Even if she switched her vote, Nanette even peddled the idea of tokhang, the archetype of police operations under Duterte’s drug war, to their neighbors in Tondo, Manila.

“Nakita ko kasi mga pulis no’n, umiikot sa Tondo. Tapos may isang drug user doon, nagtatago siya. Sabi ko, bakit ka ba nagtatago? Nagtatanong lang naman daw ‘yung pulis e. Magpalista ka, sabi ko pa nga. Kaysa nagtatago ka d’yan, magpakita ka.”

That neighbor survived, Nanette said, heaving a sigh of relief. But in hindsight, she mumbled remorse for somehow taking part in the official policy of Duterte’s brutal anti-drug crackdown.

“May mga patayan na no’n pero hindi pa rin siya gano’n kabuo sa utak ko,” she said. “Pero naaalala ko yun kasi, tinuruan ko pa ‘yung isa, na magpalista ka, magpakita ka.”

Tondo was where Rodrigo Duterte, on the night after he was sworn into office, spoke to an audience with the theme of war: “If someone’s child is an addict, kill them yourselves, so it won’t be so painful to their parents.”

Tondo was where the first in the 30,000 who would be murdered in Duterte’s six years was found salvaged, and where the last victim of his drug war would also be killed. Tondo was also where Nanette Castillo was born, where she came of age, where she would become a mother.

It was also in Tondo—along Herbosa Street, a few blocks away from the Manila North Harbor— where the life of Nanette’s first child, her beloved Aldrin, would be snuffed out in a hail of gunfire.

IT WAS LIKE A PAGE lifted off Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold.

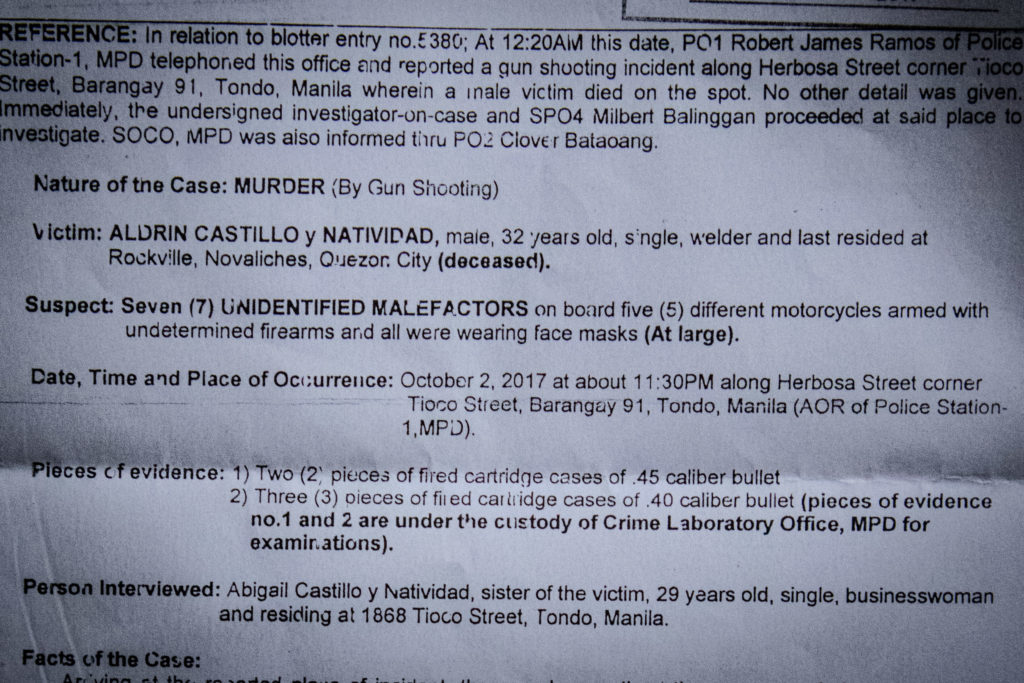

Aldrin Castillo, 30 at the time of the 2016 elections, wheedled his mother into voting for anyone but Duterte. His prophetic omen about what a Duterte presidency could execute proved to be true in her mother’s eyes on the night of Oct. 2, 2017.

To this day, in Nanette Castillo’s recollection, it’s as if everything happened yesterday.

“Nando’n ako sa bahay ng kapatid ko sa Caloocan,” she said. “Hindi ko alam, from here sa Novaliches, na nagpunta si Aldrin sa kapatid niya sa Tondo.”

Abby, Nanette’s second child and Aldrin’s younger sister, still lived in Tondo at that time. A week before that night, she asked her older brother to come over because they will buy a new television and that their air conditioner needed a repair.

Two days before his death, Aldrin had an unusual behavior: He stayed inside his room, nursing a fever. Their neighbors also noticed.

On the night of Oct. 2, 2017, Aldrin stepped out of his room. He drank with his friends on the roadside, still within the house’s first floor.

When they were about to finish, one bottle splintered into pieces. Aldrin swept off the rubble, went off to a sari-sari store, and bought new liquor. They moved nearer to a corner to continue their drinking. Their neighbors who straddled around were chatting. It was a normal night scene in Tondo, until the arrival of four motorcycles shattered the din.

Nanette had confidence about Tondo’s relative safety—her entire family lived there. The village officials knew them by name. She did not foretell the next sequences in the story.

Picking off from eyewitness accounts, Nanette recounted: “Si Aldrin talaga ‘yung pinunterya. Pinaluhod nila si Aldrin sa gitna ng kalsada. Nakataas daw ‘yung dalawang kamay ng anak ko, nakalagay sa batok. Tapos habang nakaluhod si Aldrin… tinatanong siya [kung] ano pangalan niya. Hindi na naikwento o hindi na narinig nung nakakita doon… kung nakasagot si Aldrin.”

Five bullets slammed into Aldrin’s temple, left ear, and chest. He was shot from his back, while he was on his knees.

The motorcycle-riding killers silenced him forever. On the other side of the city, Nanette jumped into another motorcycle as soon as her older sister called to break the horrible news: “Nanette, si Aldrin, nabaril.”

“Sabi nung utak ko, huwag naman sana, huwag naman sana. Pero ‘yung kaba ko talaga.”

But Nanette’s quiet refrain, incessant in her mind, betrayed her. When she arrived at the scene, onlookers were surrounding the blood-soaked area, and police officers cordoned off Aldrin’s cadaver.

Cameras were flashing. For Nanette, it was an image similar to other tokhang killings under Duterte. That was her horrid cue. She ran up to her son’s body, trying to check if there was any pulse left in him.

There was none.

It was Nanette’s confirmation: Her beloved Aldrin, 32, was dead.

IN THE HOURS, DAYS, AND WEEKS following the grotesque murder of his son, Nanette was in a daze. She could neither sleep nor cry, even if she wanted to. She felt lost. She lost her first child to vigilantes who, in Nanette’s view, felt emboldened by a president’s “kill” orders to actually kill.

Standing one foot away from her lifeless son, Nanette nonetheless tried to reach him, closed his eyes and mouth, and whispered to his ears, “Pahinga ka na.”

She noticed an odd detail around the crime scene: beer bottles used to “mark” bullet fragments. Crime scene operatives tried to hastily bring Aldrin to a mortuary of their choice, but Nanette refused.

While Aldrin lay inside a morgue, some motorcycles were circling around the vicinity, purportedly confirming if their “target” was actually killed.

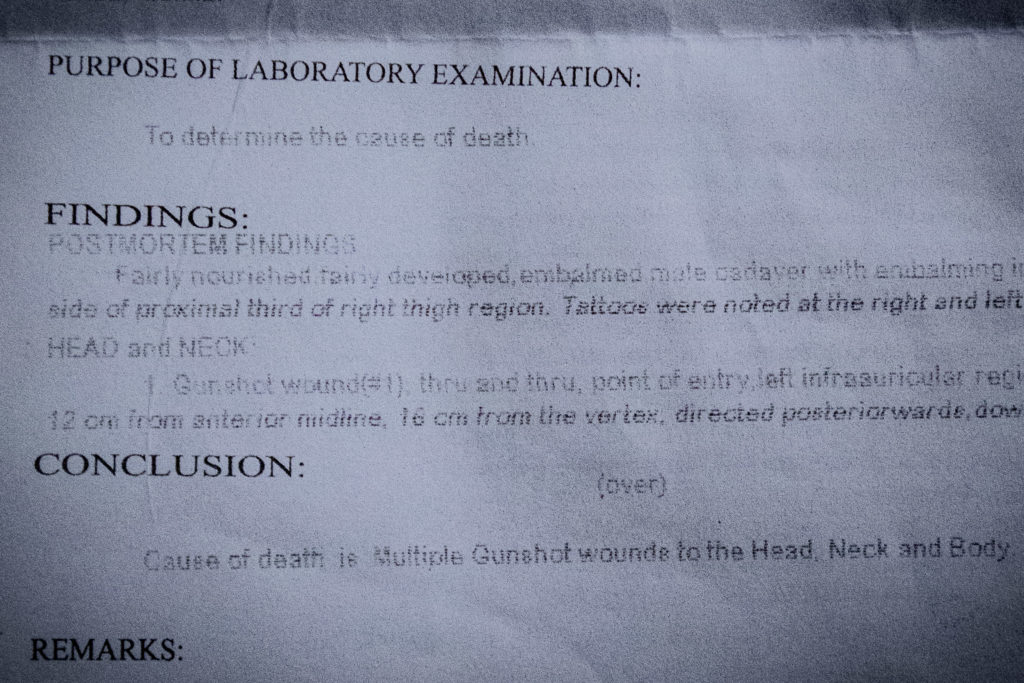

Based on Aldrin’s official autopsy report, his multiple gunshot wounds were fatal. The worst one hit his carotid artery, which made his death certain. He lost over a liter of blood due to the burst of bullets.

Two guns—a caliber .45 and a caliber .40—were used to murder him.

The memory of that night will never leave Nanette’s consciousness. “Alam mo, ang linaw-linaw sa utak ko no’n… ng mga tama [ng] bala [sa] anak ko. Diyos ko.”

Her son was almost not buried, she said, because she kept on moving the date of the interment. “Hindi ko [siya] mabitawan, kaya tumagal… hindi siya nag-sink in sa akin no’n,” Nanette said.

Her loss sunk deeper into her after Aldrin had been laid to rest.

“Hindi ako makapag-cope hanggang ngayon. Ang hirap,” she said, teary-eyed. “(Tapos) sasabihin nilang move on? Tangina, alam ba nila’ng ibig sabihin no’n?”

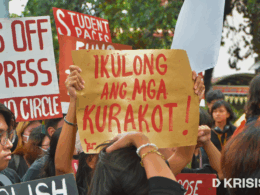

On Nov. 5, 2017, a little over a month after Aldrin’s brutal death, a group of families of other victims of extrajudicial killings under the Duterte administration held a protest across EDSA Shrine, calling for “healing.” Nanette joined them, hoping to find more avenues and allies in her personal struggle for justice.

It was the gateway to her rise as one of the brave faces of opposition to Duterte’s atrocious policies.

She volunteered for Rise Up for Life and for Rights. She showed up in media interviews. She spoke in myriad protest actions, railing against Rodrigo Duterte with his favorite curse. She joined human rights organizations.

She attended discussions that tackled, not only the killings in the drug war, but other socioeconomic issues Nanette now embraces as her own: low wages, farmers’ rights, the cause of jeepney drivers, among others.

She now works for Silingan Cafe, a small enterprise in Cubao dedicated to helping some of the bereaved in the Duterte drug war.

This became her newfound crusade.

Born in 1968, Nanette was among the “Martial Law babies.” At the height of the Marcos dictatorship, she used to join these rallies, too, but without the fervor that she now exudes. She would only relish at the sight of burning tires during protests before the 1986 EDSA uprising.

She was not a tortured anti-dictatorship activist, but she took their own march for justice as hers as well. Because of Aldrin’s murder, she had undergone what she termed as “napakasakit na pagkamulat.”

“Kailangan kong mamatayan para lang mamulat at makialam sa takbo ng bansa natin,” she enthused. “Kailangan pang patayin ‘yung anak ko ng gobyerno para lang maki-simpatya ako rito sa mga inaapi na sektor ng lipunan.”

Nanette harks back at the killing of her son with this new lens. Rodrigo Duterte and Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa, the chief architects of the drug war, are at the top of Nanette’s list of those who should be held accountable for her son’s murder and for the tens of thousands of other extrajudicial killings.

But she insisted: The village officials and police chiefs in different barangays, including in Manila Police District’s Police Station 1 which oversees Herbosa Street in Tondo, must be held to account.

The buck, she asserts, should not end with Duterte, the man she calls a “demon.”

EVEN WHEN DUTERTE stepped down from the presidency in 2022, Nanette never felt any paghilom (healing).

“Kahit naman hindi na siya nakaupo, nand’yan ‘yung mga galamay niya.”

For a mother like her who lost her only son in a vicious execution—even if the masterminds of the drug war die or are padlocked behind bars, her cries won’t stop.

“Ang hinahangad ko lang, ‘yung buhay ng anak ko, ‘yung buhay na kasama ko siya, ‘yung hindi ganito,” she said.

In her best-selling memoir about the Duterte drug war, journalist Patricia Evangelista quoted a vigilante killer who once screamed, while emptying the magazine of his gun on his kneeling victim, “Duterte kami.”

Are we?

Sipping off her glass of vodka and puffing away from her vape, Nanette snapped back.

“Hindi tayo si Duterte. Maaaring naging presidente siya, pero hindi kami, hindi tayo Duterte. Lalong-lalo na kaming mag-ina, hindi kami Duterte. Ayaw nga ni Aldrin na iboto ko siya.”

Her riposte was classic. But then again, when we traveled over seven kilometers through Quezon City during rush hour to talk with Nanette, Aldrin Castillo was seven years dead.