This story is part of our #CounterCheck election campaign coverage series. Produced independently in compliance with COMELEC regulations, this does not serve as an endorsement or campaign material.

Leticia “Ate Letty” Castillo trails a hard climb against Valenzuela’s Gatchalian republic as District 2 councilor. Yet a vibrant, youth-led grassroots campaign lends to her distinct image and the volunteer-driven movement she leads in the city.

She isn’t your typical walking politician. Not surrounded with goons and guards, but with slipper-clad kids, mothers in washed pink shirts, and forgotten citizens whose stories have never reached the heights of their city hall.

Running under the Makabayan slate, an alley-driven Castillo understands that her campaign is a way to bring the marginalized people of Valenzuela into a rights-based governance, and building heart-to-heart connections with mothers and youth are key to braving the heavy campaign trail.

“We’ll be able to reach our platforms, to reach the interests of the masses, the interests of the workers, the interests of the women, the interests of the youth. And here in Valenzuela, we’ll be able to reach them. That we are united in reaching their rights, not because we want to win,” she said.

Future is feminine, young

In a constituency where women’s voices are unheard, Letty’s atypical campaign seems to be a breather for mothers and the youth. Even in the midst of summer, the young don’t just flock to beaches — they hand out Ate Letty’s flyers not because they’re told, but because it’s fun.

“It’s a challenge for them. Because they’re young, you have to protect them while they’re participating in the campaign. At the same time, they’re learning what I’m doing. They’re also learning how to talk to the masses.”

The stories the youth share on Letty’s campaign ring louder than blaring campaign jingles.

“They’re also learning how to walk. They’re making new friends in everything we do. That’s what we see in the youth because they’re exposed,” she highlighted with utmost care and determination.

Kids don’t just tag along. They also bring their mothers too, as they have once seen Ate Letty as a beacon of change after running as one of Gabriela Party-list’s nominees in the 2022 elections.

“Our volunteers, the women, join because some of them are part of the Gabriela Women’s Party. Some of them already have jobs. So they say, it’s okay, I’ll take care of my kids. Of course, their kids are their priority,” she said.

Limited resources, constricting ties

When politics becomes personal, their struggle is shared.

“When you’re with them (audiences and volunteers), you’re talking to them from the bottom of your heart. You know their situation, their weaknesses,” she said. It becomes not just a question of winning, but why she should win.

“You’re the one who can affect them. That’s why we’re pushing. I hope I win so that I can give them what they’re asking for so that I can reach them,” Letty declared.

Despite having only over a month for campaigning, she says she never stopped her drive to talk to voters, even if logistical, financial challenges, or fatigue stop her.

“I don’t think I stopped… I really did my best [within] 40 days. You really want to win for them. You want to make a law for them.”

For her, campaigning is a journey of knowing more people, acknowledging more realities, going to untouched areas of Valenzuela she has yet to reach.

“If I’m at home and the campaign is over, you think of going back. You think that there are still places that you don’t want to go. There are still places that you want to go. There are still people that you can’t talk to,” she said.

Amidst constraints, people always brought Ate Letty a push to drive further. “It really boosts your morale. You can meet them every day. You don’t want to go back.”

It’s an ideal she promises to keep once elected.

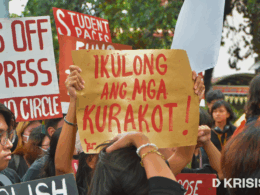

Court of public trust

However, the lack of public spaces hindered Letty’s team who once sought to organize a community caucus in a public basketball court. Their request to use it got rejected because someone was expected to use the basketball court, only for them to see it empty during the scheduled time slot.

“We asked for a letter to get a permit to use the venue. But they said that they will use it. But we found out that they won’t use it. We were thinking that maybe the enemy won’t let them use it. But even if thousands of people go there, they will still use it.”

She sees this as the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG)’s contravention of the use of public spaces for all candidates.

With or without a venue, the caucus still went on. Court or no court, Letty still believed that the court of public trust sides with them. Portable speaker in hand and folding chair on her side, she stood outside uninvited and rose unshaken for her supporters.

Her campaign is blocked yet also deeply welcomed. Even though the incumbents have the machinery, she has won the heart of the second district.

No flashy motorcades. No glaring envelopes. No glittering merchandise. Not the richest, not the loudest, yet Ate Letty always walks with her: the youth, their mothers, all under the same sun on the same streets of Valenzuela.