President Rodrigo Duterte placed Metro Manila (MM) under a one-month enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) on March 15 to minimize the spread of the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19), forcing cities in the National Capital Region (NCR) to implement curfews, social distancing, and transport freeze.

COVID-19 is an infectious respiratory disease first identified in November 2019 in Hubei province, China. It has infected over 1.4 million people and resulted in over 81,500 deaths worldwide, according to the World Health Organization’s update as of April 9.

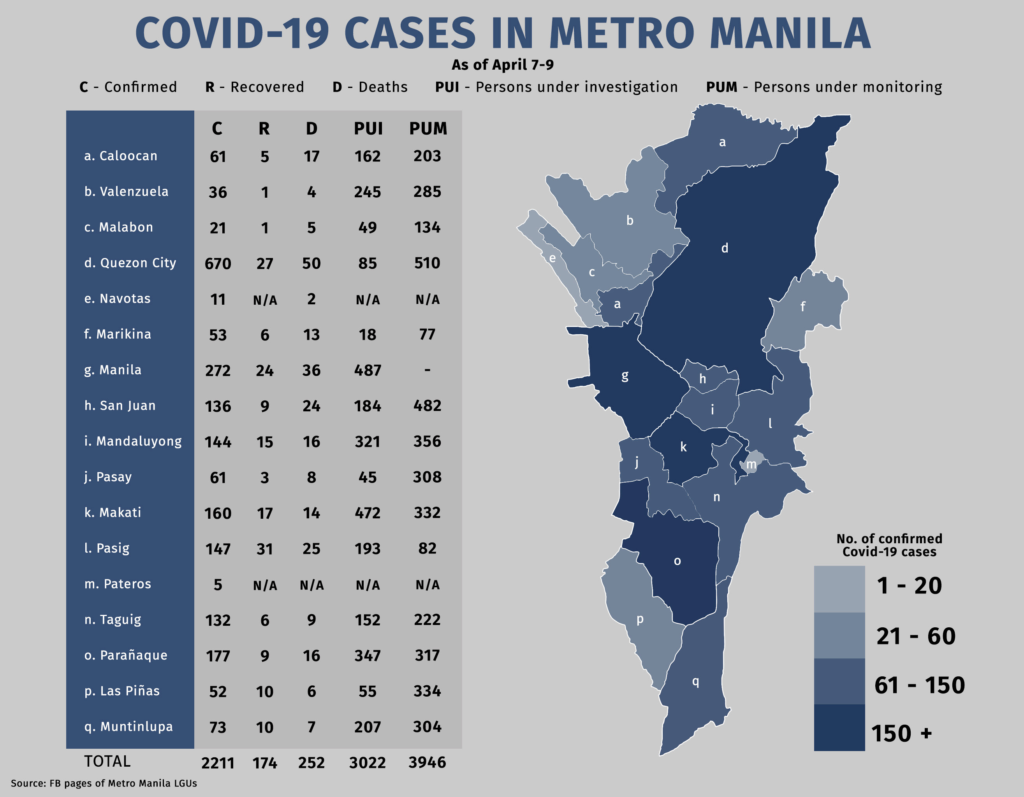

As of April 9, 54.24 percent of cases in the Philippines are concentrated in the NCR. Reports from MM’s local government units (LGUs) dated April 7 to 9 show NCR has a total of 2,211 cases and 252 deaths.

Days after Duterte’s announcement, the LGUs had to conceptualize and implement different initiatives to prevent the spread of the virus in their areas and help their constituents cope with difficulties caused by the ECQ.

LGUs’ aid to constituents

Most LGUs in the region have distributed relief goods, financial assistance, disinfection drives, and mobile markets to their constituents, with notable efforts from some cities and municipalities.

In terms of food aid, Valenzuela employed a food voucher system, while Pateros residents reported receiving six kilograms of rice and 14 canned goods per household.

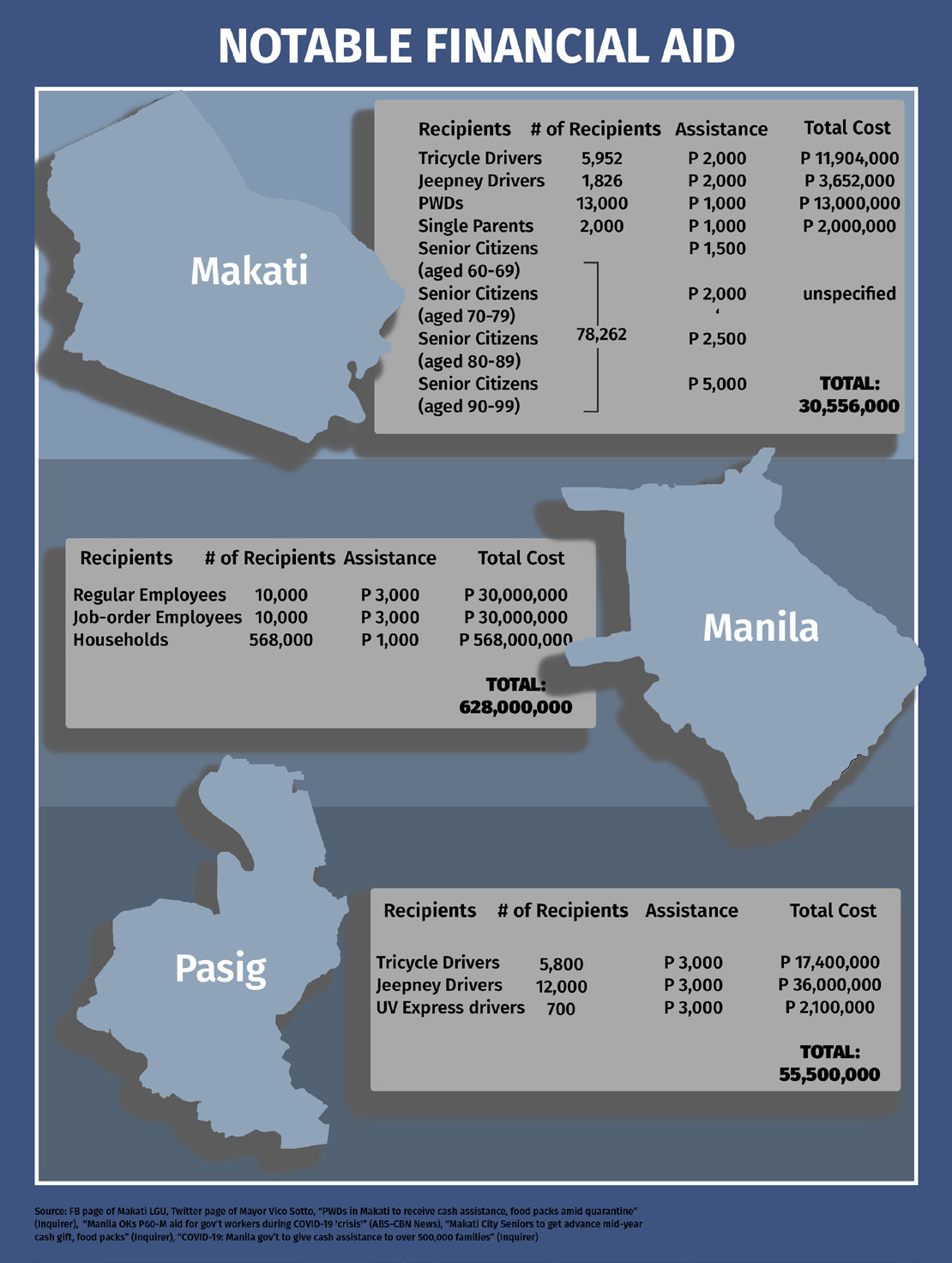

Some cities such as Makati, Pasig, and Manila have rolled out one-time financial assistance to target recipients such as drivers, workers, and senior citizens.

According to Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) Assistant Secretary Rosalinda Bautista, a family of five can survive with a minimum monthly wage of P10,727.

A worker’s minimum wage rate in Manila ranges from P500 to P537, according to the Department of Labor and Employment. Jeepney, tricycle and UV Express drivers earn from P300 to P1,000 daily.

Assuming that the financial assistance provided by these cities’ LGUs is a one-time aid, the recipients receive almost a week’s worth of daily wages, but still less than the PSA’s monthly family living wage.

Almost all LGUs in MM, except Pateros, have carried out disinfection and sanitation drives through their respective towns and barangays to ensure schools and roads remain clean to aid in the fight against COVID-19.

Schools such as the Padre Burgos Elementary School in Pasay, San Juan Science High School, Pateros Elementary School, and hotels in Valenzuela and Quezon City have been converted into isolation facilities for persons under monitoring (PUMs) and persons under investigation (PUIs).

Health initiatives and testing

Projects related to resolving the COVID-19 health crisis include the accreditation of testing centers, establishment of quarantine areas and isolation units, and free testing.

Early on, Marikina Mayor Marcy Teodoro pushed for the establishment of a COVID-19 testing center in his area. After the Department of Health (DOH) rejected Marikina’s first testing center proposal on March 26 due to location issues, the city then proceeded to build a new testing center building with DOH’s approval.

Cities such as Caloocan, Navotas, and Taguig have put up health centers where those who have COVID-19 symptoms or travel histories can get medical attention.

Meanwhile, Muntinlupa, Pateros, Pasay, Quezon City, San Juan, and Valenzuela have designated quarantine areas and isolation units for PUIs and PUMs to minimize the spread of the disease.

The processing of tests in MM has been carried out primarily by five accredited testing centers: the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine in Muntinlupa, San Lazaro Hospital and University of the Philippines National Institutes of Health in Manila, and Lung Center of the Philippines and St. Luke’s Medical Center in Quezon City.

Among the most recent additions to the accredited testing centers is The Medical City, which has recently entered into a partnership with Valenzuela to facilitate mass testing within the LGU starting April 11.

Valenzuela City Mayor Rex Gatchalian said the city government would be in charge of procuring the test, extraction, and swab kits which will be used by the hospital for their testing.

Citing increases in the estimated daily capacity for testing, National Task Force (NTF) COVID-19 chief implementer Secretary Carlito Galvez Jr. said they plan to implement mass testing by April 14 at the earliest.

Aside from formulating health-centered responses, LGUs also had to ensure that essential travel remains unhindered. Implementation of the ECQ has suspended land, sea and air travel to and from Luzon to restrict human movement and therefore limit COVID-19 spread.

Transportation

The Department of Transportation (DOTr) allowed private vehicles carrying only one passenger to leave their homes to purchase basic necessities and medical supplies.

For those with no private vehicles, LGUs and national government offices alike provided their constituents affordable transportation.

Of the 17 MM LGUs, 15 offer at least one form of public transport to carry frontliners, patients, and essential workers around their respective areas.

In Pasay, transportation is not just limited to carrying people as two M35 trucks have also been provided for the delivery of medical supplies to various NCR hospitals.

Both Manila and Pasig have taken to renting e-tricycles to provide transportation for medical workers, with the latter also launching a transportation service for patients.

Complementing these local initiatives are those operated by national government offices such as the DOTr, the Armed Forces of the Philippines, and the Office of the Vice President, all of whom offer their own free transportation services for health workers and frontliners throughout the region.

But are these efforts in terms of transportation, health, food supply, and financial aid communicated clearly and transparently to the LGUs’ residents?

Transparency

Each LGU posts on their respective Facebook pages to update their constituents of programs being undertaken to alleviate financial and food shortages brought about by the pandemic.

Among them, Navotas has shown to be transparent compared to its counterparts. The city’s Facebook page provides daily updates on the number of relief goods distributed in various barangays, as well as daily reminders on which areas are getting visited by their mobile market program.

Pasig does not often post on which areas have been covered by relief goods operations, but they do give daily updates on their Mobile Palengke program, COVID-19 health reminders, and other related projects.

Makati, Parañaque, and Taguig have been proactive in sharing which areas have been given financial and food aid, but their updates are often filled with comments from residents saying they have not received relief goods or cash assistance yet.

Manila, Caloocan, and Pasay, which all have more than a hundred barangays, are struggling to provide aid in their areas, as shown by the lack of updates on relief efforts and feedback from their constituents.

The municipality of Pateros does not often post its current operations against the virus nor provide daily updates on COVID-19 cases in their town.

Assessment of the responses

Whether through distributing relief goods or financial assistance, spearheading health-related initiatives, or organizing transportation for essential travel, all LGUs have done their part one way or another to assist their citizens in coping with the crisis.

The overall response, however, has been varied at best. Without a coordinated masterplan for all the MM cities to execute in times of health crises, LGUs have no choice but to formulate and implement projects that consider their budget, their constituents’ needs, and judgment of elected local officials.

Almost a month into the quarantine, the disparity between how Pateros provides six kilograms of rice and 14 canned goods compared to Pasay’s relief packs with two kilograms of rice and two to four cans of sardines, or how several residents in Quezon City and Manila claim they have not received relief goods could cause further unrest, especially in cities where LGUs are not as efficient in distributing essential help.

Despite a lack of coordination in governance, LGUs are united in their desire to stop the spread of COVID-19 and help their constituents get through the ECQ. Only time and eventual feedback from the people will tell whether such efforts prove effective.

This article first appeared in KRISIS (AY 2019-2020) – COVID-19 Pandemic Issue on April 12, 2020.