In his post-war polemic about the debasement of language for political expediency, Politics and the English Language, George Orwell wrote this salient sentence: “But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.”

He might have referred as well to the recent Senate investigation into the previous administration’s war on drugs.

The public hearing, in which former president Rodrigo Duterte himself had attended, featured mesmerizing twists and turns. But one peculiar debate during the eight-hour deliberations focused on a single English word.

Neutralize.

In chemistry, it refers to rendering something chemically neutral. But the second definition offered by the Merriam-Webster dictionary rings more bells: “[T]o counteract the activity or effect of : make ineffective.”

If an official national security directive foregrounds the neutralization (or negation, in some cases) of suspected elements identified by the government, is it tantamount to their deaths during security operations?

This was at the heart of a heated argument between human rights lawyer Jose Manuel “Chel” Diokno and Senator Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa during the Senate hearing on the Duterte government’s drug war, Oct. 28.

Based on a copy of Command Memorandum Circular No. 16-2016, which launched the anti-narcotics crackdown under Oplan Double Barrel, Diokno argued that the presence of the terms neutralization and negation without a strict definition gave a freer leeway for police officers to construe them on the ground.

Quoting erstwhile police spokesperson Senior Supt. Dionardo Carlos’s statement in 2016, and analyzing how the Philippine National Police (PNP) interpreted the terms, Diokno concluded that neutralize or negate meant “to kill” drug suspects.

A riled up Dela Rosa fired back: “Is it really killing, killing, killing? Otherwise, kung gusto kong patayin ‘yung mga suspek na ‘yan, bakit pa ako gagamit ng neutralize na term? Gagamitin ko na lang ‘to kill, to kill, to kill.’” He also cited the Google definition of neutralization.

For his part, former PNP chief Gen. Archie Gamboa made a strong defense of neutralization in police parlance. “If you take in its entire context,” he insisted, “you don’t necessarily mean neutralization is killing.”

Also a lawyer, he added: “Mahirap kasi ‘pag kunin mo ‘yung context na iisang page lang, or dito ka lang sa neutralization […] Take the interpretation in its entirety. Hindi lang doon sa neutralization.”

But in the fuller context of state security, how the operational definition and use of neutralization has been established historically becomes innate to the discussion. The Senate Blue Ribbon subcommittee failed to delve deeper into this aspect.

Take for instance an Aug. 7 report from the Philippine News Agency on “neutralized” alleged communist rebels: “‘Neutralized’ in military parlance collectively refers to the surrender, arrest, and death of insurgent members or supporters.”

When the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) announced the deaths of Isnilon Hapilon and Omar Maute as the war in Marawi neared its end, the military’s official statement called their demise as “neutralization.”

Dela Rosa himself, when he was still the police’s top honcho in 2016, used neutralize to refer to a bounty from alleged “narco-generals” in a plot to kill him.

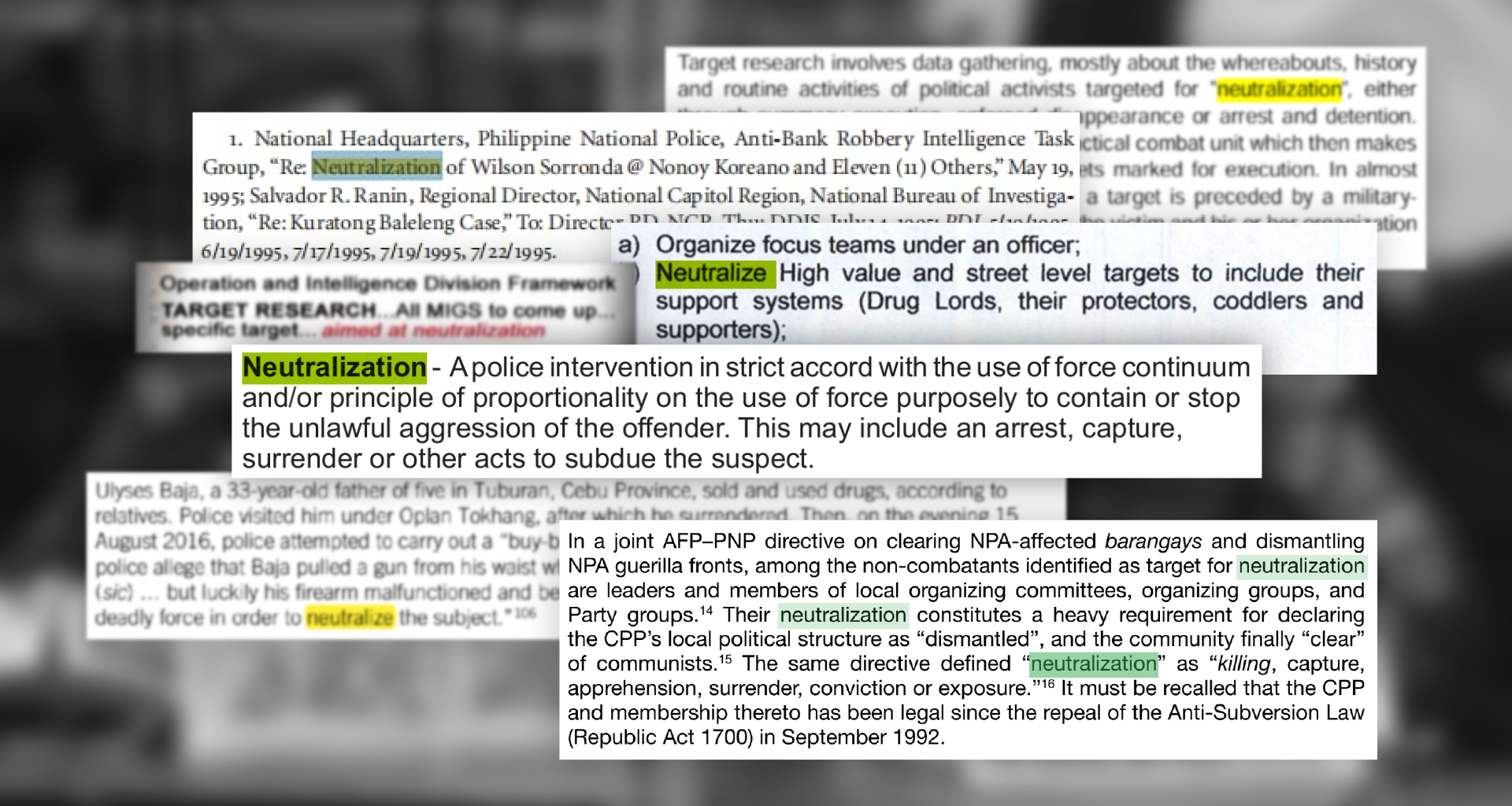

The 2021 Revised PNP Operational Procedures manual strictly defined neutralization: “A police intervention […] to contain or stop the unlawful aggression of the offender.” It listed acts that may fall under it: arrest, capture, surrender, or “other acts to subdue” the suspect.

However, a 2017 Amnesty International report averred that neutralization has always been a “common euphemism” for killing in the Philippines, much similar to how the Marcos dictatorship’s abuses bastardized the word salvage.

A more historical approach in analyzing how it had been taken into account operationally further reveals a longer tradition of the word serving as a code for death or killing of suspects.

For instance, Kuratong Baleleng leader Cpl. Wilson Soronda and eleven of its alleged members were killed in two separate incidents on May 19, 1995. The eleven suspects were loaded into a van and were brought to a Commonwealth Avenue flyover, where they were executed in a rubout fashion.

Soronda, meanwhile, was accosted on the other side of Metro Manila. According to the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI)’s report, his body was dumped in an apartment in Pasig City, where police officers from Task Force Habagat—under the tutelage of Supt. Panfilo Lacson—shot at his cadaver to claim that he “grabbed a firearm.”

The NBI dubbed them as “pure and simple summary executions,” but the report to the police’s national headquarters referred to these deaths as the neutralization of suspected criminals.

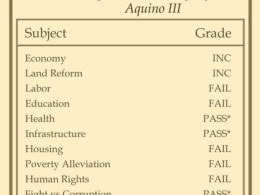

The juxtaposition of its semantic and operational existence is more evident in how former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s generals carried out Oplan Bantay Laya (OBL) I and II, her regime’s counterinsurgency pogrom.

A compendium published about OBL noted that in the course of its military operations, a “joint AFP-PNP directive” indicated neutralization as the “killing, capture, apprehension, surrender, conviction or exposure” of suspected communist leaders listed in state forces’ Order of Battle and identified as non-combatants “targeted for neutralization.”

In 2004, according to a separate documentary about Arroyo’s “all-out war” against communists, an intelligence document from the military ordered its intelligence units to identify “specific targets” who are “aimed at neutralization.”

The translation on the ground was the killings of 1,206 activists whom soldiers tagged as underground cadres.

United Nations Special Rapporteur Philip Alston emphasized this trend on how the Philippine military operationally used the word in his 2007 report about human rights abuses under the Arroyo administration, as well as other local human rights records.

Decades before Arroyo’s OBL, in July 1986, the US Army published Field Circular: Low Intensity Conflict, the codification of Washington’s “special warfare doctrine.” The military adopted it in the course of the Cory Aquino administration’s tussle with communists.

The document still upheld “eliminating or neutralizing the insurgent leadership”—which, according to historian Alfred McCoy, “repressive third world militaries could readily construe as a recommendation for selective assassination.”

Even in the early months after Duterte rose to power, this treatment of neutralization in ground operations had been maintained. The 2017 Amnesty report cited the case of Ulyses Baja, who was killed in a police buy-bust operation in Tuburan, Cebu. The official spot report on Baja’s death indicated that he allegedly drew a firearm, but it failed, forcing the police team to “[resort] to deadly force in order to neutralize the subject.”

Gamboa’s assertion that neutralization must be taken in its whole context was valid. Yet a historical understanding of how the term, in semantic and operational purview, came into being offers a clear picture.

More often than not, neutralization equated to fatal operations that killed suspected criminals or rebels. In local state security lexicon, neutralization was never a neutral term.

Its manifestation in the context of Duterte’s drug war—from CMC 16-2016 to the Oplan Double Barrel’s implementation plan—and in the administration’s Development Support and Security Plan Kapayapaan must be scrutinized in light of neutralization’s entire historical context, both in word and in praxis.

After all, no less than former president Duterte himself flaunted his own operational perception of the word when he spoke before the 803rd Infantry Brigade in Camp Juan Ponce Sumuroy in Catarman, Northern Samar.

He advised soldiers that their best way to go after communist rebels was to “step up” intelligence work.

“Then once you get them,” the commander-in-chief intoned, “it’s neutralization.”

Chris Josef de Jesus contributed research to this story.