A ribbon was cut, but the opening of Robinsons Easymart in DiliMall was anything but a celebration.

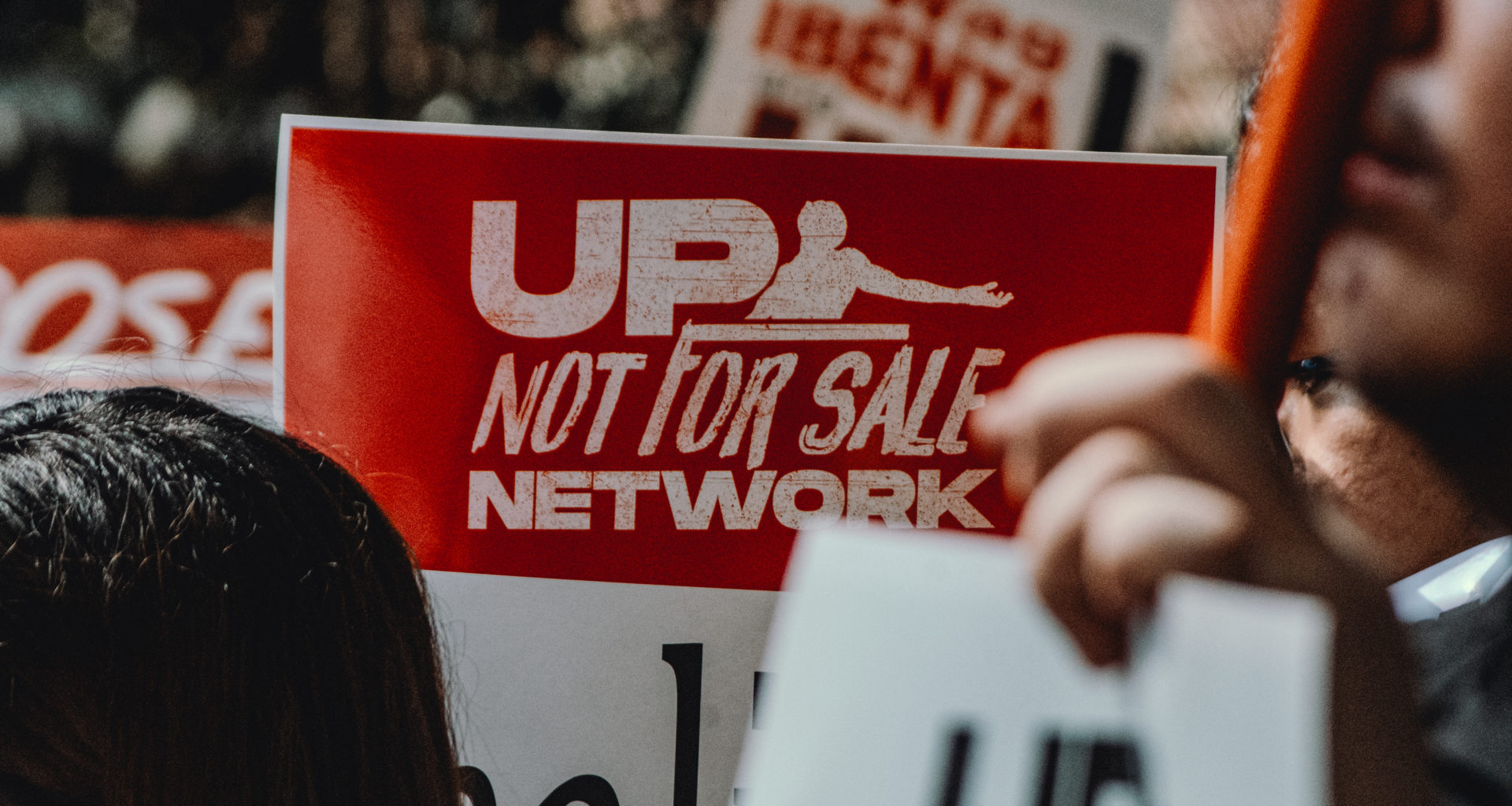

Students, stallholders, and advocates stood in protest, their chants and banners challenging the narrative of progress the University of the Philippines (UP) sought to project. For them, this was not just the opening of a grocery but the nail in the coffin of a saga marked by displacement, commercialization, and neglect.

What should have been a triumphant return of a central campus space instead raises unsettling questions: Who benefits from DiliMall? What do its operations say about the university’s priorities? How does its presence reshape the fabric of the UP community?

The story of DiliMall is one of misaligned incentives. At first glance, it promises modernization: a sleek, multi-story retail hub managed by a third-party operator, CBMS-RMCS. The deal seemingly liberated UP from the burdens of daily operations, allowing the university to focus on academic pursuits.

But beneath this polished exterior lies a business model that raises more concerns than it resolves. Stallholders who once operated in the old Shopping Center now face rents as high as P350 per square meter, compounded by a 7% sales fee and 5% service charge—costs that are untenable for many small vendors.

The rental terms tie UP’s revenue to the mall’s occupancy rates and tenant sales, leaving the university vulnerable to market forces beyond its control.

This setup not only jeopardizes UP’s financial stability but also marginalizes the very stakeholders it claims to support. The displaced stallholders–whose businesses once provided affordable goods and services to students—now struggle to compete with corporate tenants occupying the prime ground floor spaces.

Mainstream retail establishments represent a gentrified vision of commerce, far removed from the community-driven ethos of the original Shopping Center.

Beyond these immediate business concerns lies a deeper issue: DiliMall exemplifies a broader trend of commercialization within UP.

This trend, often justified by budget shortfalls, has seen public spaces increasingly leased to private corporations.

From Ayala Technohub to GyudFood, UP has prioritized revenue generation at the expense of its core mission as the nation’s premier academic institution.

The rise of DiliMall underscores this shift in priorities. Its construction not only displaces small vendors but also transforms the campus landscape, replacing inclusive spaces with exclusive ones.

Vendors who once operated at the Old Tennis Court are now being moved to make way for a parking lot, further marginalizing the campus’s most vulnerable workers. Meanwhile, students face higher prices for goods and with even less access to affordable dining options, eroding the accessibility that once defined campus life.

This displacement of long-standing vendors and the rising cost of everyday goods are direct consequences of a business model that prioritizes corporate interests over community needs.

From a triple bottom line perspective, this situation highlights the failure to balance economic, social, and environmental responsibilities.

While the economic returns from higher-end tenants might be attractive in the short term, they come at the expense of the social equity that should define a public institution like UP.

The campus is meant to be a space that serves all, particularly the most marginalized, yet this new retail landscape disproportionately benefits corporate entities while leaving behind small-scale, local vendors.

By prioritizing profit through high rents and corporate tenants, the administration is contributing to economic inequality, where students and the broader UP community are priced out of the basic services they once had access to.

This erosion of community values extends beyond economics. The lack of transparency and consultation in DiliMall’s planning process betrays UP’s commitment to participatory governance, a cornerstone of social responsibility.

Despite protests and calls for dialogue, many stakeholders–including the displaced vendors, students, and faculty–were excluded from critical decisions regarding the development of this misplaced edifice.

This top-down approach reflects a troubling disregard for the voices of those most affected by the university’s commercialization policies.

Yet the controversy surrounding DiliMall is not without solutions. The pressing need for a strategic shift, however, requires a fundamental reconsideration of UP’s role in shaping its future and the future of its community.

The administration must not simply fulfill its obligations to displaced stallholders by offering fair rental terms and accessible spaces. It must recognize that equitable economic participation is not a courtesy, but a fundamental right of its constituents.

The financial strains imposed on these small vendors are a clear manifestation of structural inequality, where economic growth is pursued at the expense of those who have long contributed to the fabric of campus life.

Fair rental terms are not enough. The commodification of public spaces, which has become a hallmark of neoliberal governance, should not be UP’s guiding principle.

UP must protect its public good—a space where knowledge, culture, and community converge. It should reject the notion that profiteering and economic efficiency should take precedence over social justice.

This is a moral responsibility for any institution that brands itself as a sanctuary for the marginalized, a space of hope and transformation.

The university cannot afford to disenfranchise its own people—students and vendors alike—simply to secure temporary fiscal relief through corporate partnerships that leave behind those who can least afford it.

Beyond honoring commitments, the university must embed transparency as the very backbone of any move towards development initiative.

The lack of consultation in DiliMall’s design and management reflects a more pervasive failure within UP’s institutional culture: the disconnect between power and the community it is meant to serve.

The university must move beyond tokenism in decision-making and embrace true democratic participation in shaping the spaces where its students, faculty, and workers live and learn.

This is not a minor administrative adjustment. It is a foundational shift that requires systemic change—where the voices of students, faculty, and vendors are not just heard but actively integrated into every stage of planning, execution, and review.

The pursuit of fiscal autonomy through commercial ventures should not justify the dilution of public trust or compromise the institution’s core mission.

Public institutions like UP should never become commodities in the free market, where educational values are undermined for corporate profit.

Alternative revenue streams aligned with UP’s vision—such as research-driven initiatives, partnerships with social enterprises, and philanthropic funding—must be explored. These can provide UP with sustainable income while protecting its integrity as a public institution that serves the greater good.

The opening of Robinsons Easymart in DiliMall isn’t just the beginning of a new retail venture. It’s a critical juncture that forces us to confront the direction in which UP is heading. It forces us to ask what development truly means and who it ultimately serves.

It is time for UP to reset the narrative. The university must step up and lead by example—demonstrating that development and social responsibility are not mutually exclusive but are in fact intertwined. It must listen to its people, protect the most vulnerable, and prioritize inclusivity in every decision.

The future of DiliMall and the future of UP rests in the hands of the administration. Will UP remain a beacon of hope for the many, or will it become a symbol of exclusion?

The time to choose is now. The people are watching.