Former president Rodrigo Duterte appeared before the first Senate probe into his brutal war on drugs on Oct. 28, punctuated with the same swagger and bravado that had once attracted 16 million voters into electing him to the highest position in the Republic. He employed the familiar bluster, the resounding violent rhetoric, which turned his appearance into an awful throwback to the days of his rule.

The first words Duterte uttered before the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee set the tone for a staccato of admissions that he would eventually spill through the eight-hour hearing. He thanked the senators for the invitation, requested them to treat him as a witness, not a former president, and looked forward “if the truth will come out.”

Invoking the mandate that came with his presidential power, Duterte opened: “Do not question my policies because I offer no apologies, no excuses. I did what I had to do, and whether you believe it or not, I did it for my country.”

The mantle of the presidency did not come with any guarantee that a leader can kill as he pleased, but Duterte believed otherwise.

The former leader’s opening statement turned into a barrage of contradictions.

The drug war, in his purview, was launched at the altar of the “innocent and the defenseless,” but they were the first ones to die in his war. It was about the “elimination” of illegal drugs, he claimed, but the illicit trade flourished throughout his presidency, not when his former economic adviser Michael Yang was a notorious Chinese drug lord, if the public takes Col. Eduardo Acierto’s words for it.

Duterte made a parallelism between his war and other “wars”: Wars against waste, against corruption, against climate change. But in the other wars he mentioned, there were little to no corpses that littered the streets of the country.

He viewed drug addicts, or so he claimed at first, as “victims and patients” that required “medical attention.” In the contradictory world of Rodrigo Duterte, was that attention the surgical strikes against 30,000 alleged drug addicts, users, and pushers?

His introduction into his testimonies was a balderdash, because his litany of confessions followed through.

Yes, he encouraged suspects to fight back to justify their killings. Yes, he ran a death squad—but without police involvement.

But maybe all the top cops who served in Davao City ran the death squads: Archie Gamboa, Vicente Danao, Catalino Cuy, Romeo Caramat, and that bald-headed member of the committee, Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa.

The contradictions, a hallmark of the Duterte (under)world, held on.

“I and I alone take full legal responsibility sa lahat ng nagawa ng mga pulis pursuant to my order. Ako ang managot, at ako ang makulong, huwag ‘yung pulis na sumunod sa order ko, kawawa naman nagta-trabaho lang,” thundered the man who howled at “my police and soldiers” to kill those “sons of bitches who were destroying my country.”

But when Sen. Risa Hontiveros confronted him if he will assume responsibility for the brutal deaths of Kian Delos Santos, Karl Anthony Nuñez, and other young victims of his drug war, Duterte backtracked, screaming back with a callow “guilt is personal” excuse before he bowed out during the recess.

“To claim to be a killer while repudiating killers—this was the magical reality of Rodrigo Duterte,” wrote journalist Patricia Evangelista in her thought-provoking, acute “memoir of murder” in the Philippines.

That magical reality resurfaced when Duterte, the joker, the unconventional politician, and the self-confessed murderer, sat before the upper chamber.

He felt comfortable with his doublespeak in front of the senators. Two of his drug war’s supreme cheerleaders and architects, Dela Rosa and Bong Go, unabashedly arrogated upon themselves the pristine task of investigating the Frankenstein of their own creation. It did not bother Sen. Aquilino Pimentel III, the committee chair, that the two who should have been standing as witnesses had taken part instead in the scrutiny of their bloodied war.

The absolute necessity of holding to account Duterte and his acolytes who masterminded, orchestrated, and carried out his murderous vision of cleansing out illegal drugs and crime, must be as undisputed, unyielding, and unflappable as their own denial—or confession, if it suits—of participation in the mass murder.

Rodrigo Duterte was both an aberration to the status quo, and a violent perpetuation of it.

In line with his brand of contravention, Duterte was, at once, a savage interruption of the normal, and a reminder that his new normal isn’t actually new, only that the “normal” of the past was couched in Georgetown-educated language.

Duterte was Ferdinand Marcos Sr., who enacted Proclamation 1081 under the false veil of stamping out the communist menace, claimed that no political prisoners existed in his stockades while hiding his rivals in torture chambers, and justified the murder and abductions and massacres of his New Society.

Duterte was Fidel V. Ramos, who promoted intemperate police officers like Panfilo Lacson and Reynaldo Berroya into the higher echelons of his police force, embellished them as “super-cops,” and unleashed a brutal campaign against criminal syndicates that almost mirrored Duterte’s own “war.”

Duterte was Joseph Estrada, who exalted the ruthless rubout of 11 suspected criminals along Commonwealth Avenue by his officers under the Presidential Anti-Crime Commission in 1995 and boldly asserted that they “don’t deserve sympathy […] it’s just right that they were exterminated.”

Duterte was Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who applauded Major General Jovito Palparan and his howling wilderness in Central Luzon in her State of the Nation Address, rewarded the butchers in her army with promotions and protection, and who almost installed herself as a dictator after squaring off with mass revolt.

Duterte was also Corazon Cojuangco-Aquino, who unsheathed the “sword of war” after communist leaders walked out of negotiations in the wake of the killings of farmers in broad daylight.

Duterte was also Benigno Aquino III, who said “there is no campaign to kill anybody in this country” while Lumad leaders in Mindanao were being murdered in cold blood.

His ferocious police force was also an offshoot of the long, merciless legacy of policing that the country bequeathed from its American colonial masters and configured into its own bloodbath. They were Jovito Palparan, Eduardo Año, Hermogenes Esperon Jr., Cesar Mancao, and Michael Ray Aquino.

They were the criminal torturers of Marcos Sr.’s martial law regime. They were the nefarious goons who led Ninoy Aquino off the plane, down into the jetway stairs, where his public execution awaited. They were the foot soldiers of Aquino and Estrada’s all-out wars. They were the uniformed men who slammed bullets into hapless farmers in Mendiola, in Hacienda Luisita, in Kidapawan—or the masked killers who used a backhoe to dig a mass grave in Shariff Aguak.

The Davao Death Squad wasn’t also novel. It had the trappings of Civilian Home Defense Forces, CAFGU, Alsa Masa, Magahat-Bagani, Tadtad, and the other death squads that had once made headlines with gory images of death. In fact, Col. Ronald Dela Rosa was once the face of Tadtad.

Rodrigo Duterte and the police force he galvanized for his murderous drug war came from a mercenary tradition that assaulted, brutalized, and cudgeled the “enemies of the people” with the barrel of the gun for decades.

The only demarcation separating the country’s violent past and Duterte’s brutal present was the fact that he was uncouth, daring, and unforgiving in his murderous policies. He refused the temptation of palliating his “kill” orders.

He invoked “kill” 1,254 times in the first six months of his war. He goaded his dogs to kill suspects, kill the idiots, kill them all. Along with his fanatical followers, he incited them to shoot female rebels in the vagina, to kidnap state auditors, to kill bishops, to “finish off” communists, and to shoot human rights activists.

When faced with the brazen killings of 32 suspects in one night, and in one province, Duterte sang praises: “Maganda ‘yan. Makapatay lang tayo ng mga another 32 everyday, then maybe we can reduce what ails this country.”

In his first months in Malacañang, Duterte averred: “[Adolf] Hitler massacred three million Jews. There are three million drug addicts. I’d be happy to slaughter them.”

No Philippine president was as audacious and brazen in his declarations to kill his own citizens as Rodrigo Duterte. That was his consequential anomaly into the “normal” of violence in the country’s barbaric past.

The other deviation was this: Past administrations were hounded with protests when their policy included the colossal violation of human rights. The two EDSA uprisings were also a rejection of the ousted regime’s abuse of its power. But when Duterte scowled for blood, there was laughter, cheering, and approval. It had the “permission of my people,” in Patricia Evangelista’s words.

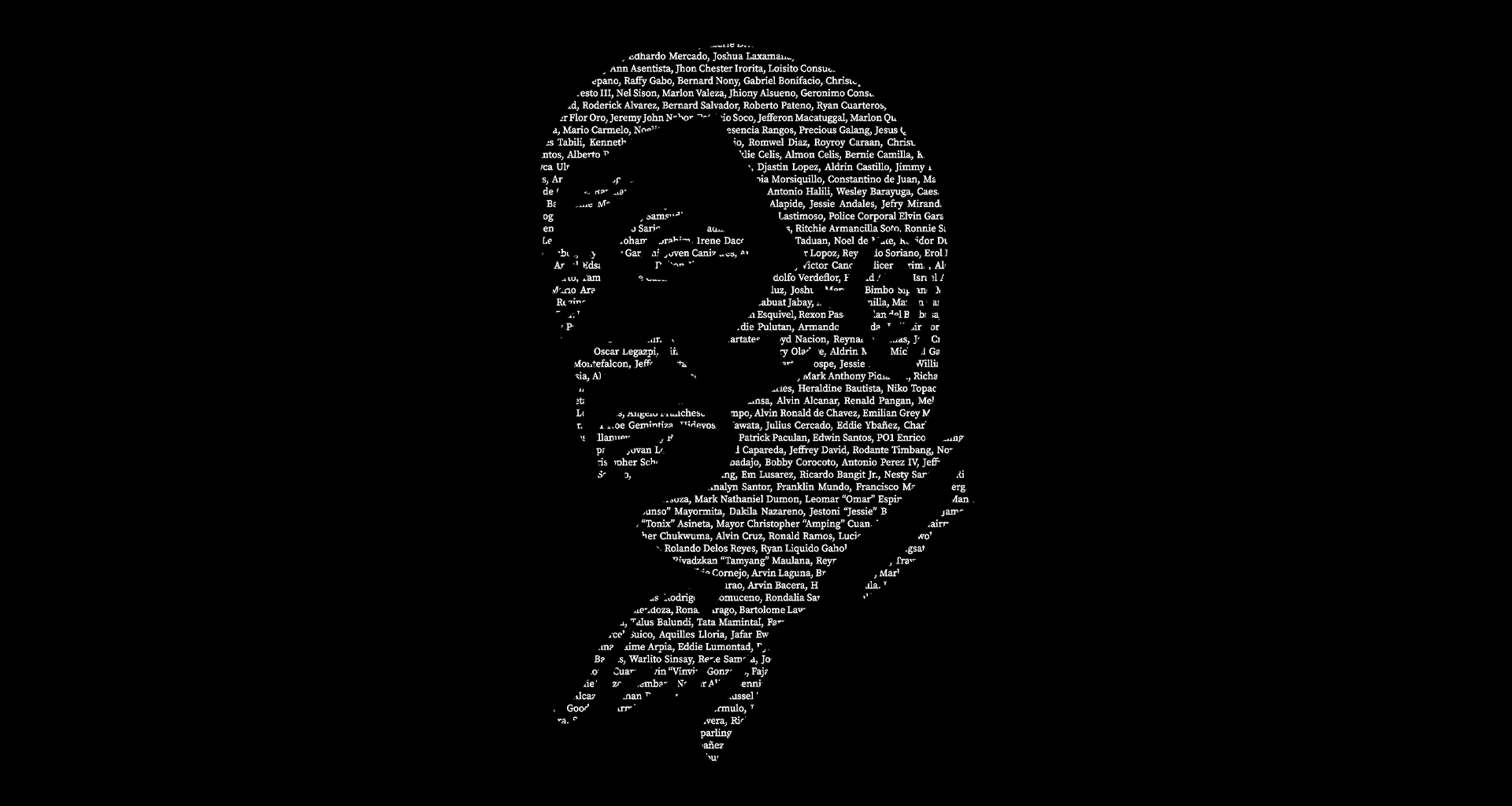

But the madman in whose name tens of thousands were executed—20,322 from July 1, 2016 to Nov. 27, 2017, according to the Supreme Court—is no longer in power. He is now stripped of presidential immunity.

His dismissal of the International Criminal Court and of the House of Representatives’ own inquiry into his brutal anti-narcotics crackdown bears no weight. Even if he continues to bluff his way out of accountability, shields himself from it, or runs away as far as his overstretch could, history is making its final verdict.

Rodrigo Duterte is culpable for the killings that snuffed out the lives of his own people.

Even if his cheerleaders remain steadfast in applauding his horrendous legacy, and even if he scribbled his unique gospel of murder around a mercenary tradition of the state forces that preceded him—and will outlive him—Duterte has to face his day of reckoning for the bloodshed in his own iron fists.