Bernardita Omay first stepped on land belonging to the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman with her nine children on July 30, 1996, hoping to find a place to stay after they left Samar to find better opportunities in the city.

A few weeks in, she was confronted by officials of UP’s Office of the Community Relations (OCR) who told her family that squatting on UP land is prohibited by the university. Omay was brought to the OCR office and was told that her family would be given an allowance to return to Samar.

But, the office said, it first needed to pool its funds for this and that this would take several weeks. Omay went back to her ramshackle shanty on an empty lot in Pook Malinis, a few kilometers from the university proper, and broke the news to her children. Then the waiting began.

Today, 20 years later, Omay is serving as the coordinator for Pook Malinis — the go-to person for the community that has grown from just a handful to at least 755 households last year. Two of her nine children have long graduated from college. Four have found their way back to Samar to start their own families. But the rest still live with her in their small house in Pook Malinis.

Omay and her family have made it through several attempts of the university to demolish her home and those of her neighbors. In between those 20 years, the OCR has closed down, only to reopen in 2010. She and her family still patiently wait for relocation, long overdue.

The enduring presence of Omay and informal settlers on UP’s vast land is a stark reminder of how UP has failed to solve the informal settlers’ problem, even after then UP Diliman Chancellor Caesar Saloma adopted in 2011 a policy to “contain” the proliferation of Informal Settler Families (ISFs) in the campus.

Saloma’s containment policy

At a general assembly held Dec. 8 that year, Saloma announced that the university would start prohibiting the construction of new informal settler structures on its land, and dismantle units built after January 2012. Results of a census conducted by his office, in coordination with the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Community Affairs (OVCCA), showed more than 70,000 informal settlers were occupying 11 to 15 percent of the 493-hectare land the university owned, spread out over 14 pook (neighborhoods). Under the proposed 2012 UP Land Use Plan, the university was to convert “unused” land into a combination of faculty and staff housing, and resource-generating facilities such as the UP Town Center.

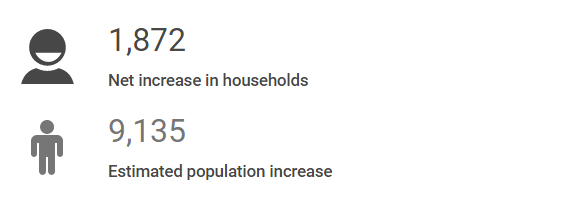

But the opposite has happened in the last six years. The burgeoning population of informal settlers has been blamed on an administrative failure to dismantle new illegal structures, the illegal sale of university land on new tenants, and conflicts between the Quezon City government and the university which led to a mismanaged relocation program.

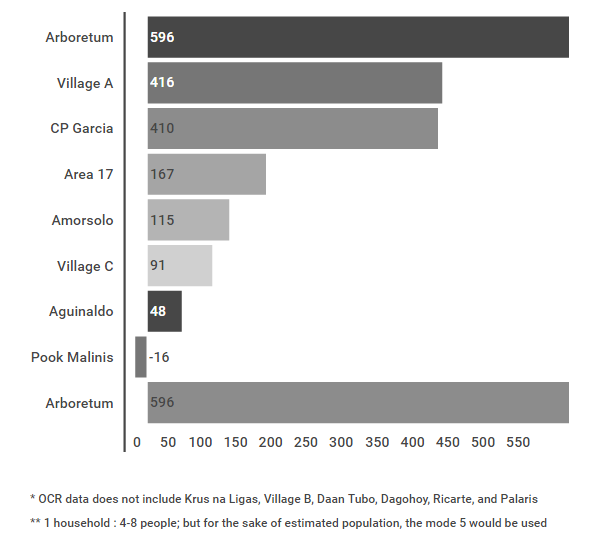

When Saloma assured the chancellorship, Diliman was home to 8,327 informal settler households. The number rose by 22 percent to 10,154 households in 2016. Most are self-built unit (SBU) households, which from the name itself means built through the personal means of the corresponding family, without permission from the university. Household is defined by the university as being composed of four to eight people.

Of the 14 SBU areas found in UP, communities like Area 17, Dagohoy, and Villages A, B, and C are within campus grounds, while Pook Arboretum, Pook Amorsolo, and a few others are located outside the university gates.

The OCR monitors the households in all 14 community populations. According to their data, all but one have posted increases in the number of households. Pook Amorsolo registered the highest growth at 36 percent, from 319 to 434 households in the last five years.

Outnumbered, outmanned

Bea Maura, formerly a Community Relations Officer from the OCR, explains that that the increase in SBU households can be attributed to the fact that the Anti-Squatting Task Force of the UP Diliman Police (UPDP) has been unable to implement university policy. The Task Force personnel are tasked by the UPDP to dismantle new illegal structures, prohibit the arrival of new illegal tenants, and monitor for possible illegal activities. However, due to the lack of resources, the Task Force has not been capable of implementing said policies on all 14 SBU areas.

“Unfortunately, the Task Force does not have enough members. So, the numbers keep rising because the policies cannot be implemented. Many illegal structures popup, and so does the number of informal settlers,” she said.

While the containment policy is relatively new, the prohibition against illegal settlers have existed since the 1980s It was during that time that then UP President Edgardo Angara implemented a policy titled the “Prohibition of the Sale, Donation, or Assignment of Privately-Owned Houses,” which prohibits UP faculty, who were given free housing, to sell or rent their residences. The policy states that “any and all such sale, transfer, or assignment (of SBUs) is null and void and will not be recognized.” And yet, the number of informal settlers has increased to nearly 10,000 new residents.

However, according to Omay, the increase should be blamed on the OCR’s lack of strict implementation instead. “They say that renting is prohibited, but nothing happens to them anyway. Many are building their own houses without permits but are not seen (by the OCR). Neither are they recorded by the census-takers,” she said.

Ideally, said Mauro, the Task Force conduct regular walk-bys around the 14 SBU areas in the university to check for new structures. They then ask the affected household to “self-demolish” the structure. If this fails, the Task Force member conducts the demolition with help from the UPDP.

This isn’t the case however, said Omay, as not only are community visits by the OCR and Task Force rare — around one every two months — they often miss new structures under construction. These structures, when finally spotted by members of the Task Force, will already have been housing several ISFs and cannot be easily dismantled. And then the process repeats itself.

Regine Briones, C.P. Garcia Block 1 resident and head of the neighborhood association, said the continued increase of informal settlers such as her can be attributed to a lack of livelihood opportunities in the communities. While no exact data is available, Briones said that most residents barely scrape a living by selling scrap or begging for alms in the university grounds.

“Maybe because of sheer poverty, residents divide their homes into livable rooms which they can then rent out to outsiders. They don’t get caught because they do it in secret anyway,” she said. Briones then points out several houses containing seven to eight families, all of whom are renting illegally.

With the staggering growth in ISFs, UP needed a comprehensive resettlement strategy.

The three-year plan

On June 20, UP Diliman Chancellor Michael Tan and Quezon City (QC) Mayor Herbert “Bistek” Bautista signed a memorandum of agreement that kickstarted the three-year resettlement plan to house the 55,000 ISFs residing in the city’s project zones, which include Barangay UP Campus among seven others.

Bautista added that the successful resettlement of the community would “fast-track the continuation of suspended construction projects from 2012 to 2015” and would improve traffic flow in Metro Manila. Possible relocation sites for ISFs within UP include Bistekville in QC, or select areas Rizal, Bulacan, and Cavite through the National Housing Authority.

“If the national government would just address the traffic, and disregard our ISFs, then it defeats the purpose of poverty alleviation, social inclusivity and development of our country,” Bautista said in one of his press conferences.

Prior to the resettlement proper, the OCR were tasked to conduct surveys and profiling of ISFs within the priority areas in UP, C.P. Garcia and Village C. According to the OCR, after the profiling, they will then create a formal resettlement action plan, in consultation with the communities.

At the same time, however, construction projects by the university are in full swing as resettlement efforts stall indefinitely. These projects include the ongoing construction of new faculty and staff housing along E. Jacinto Street, likely to affect the residents of Village C.

According to officials from the OCR and OVCCA, the construction will claim the land where Village C sits, but a resettlement plan is yet to be concretized. Caught between the university’s plans for new infrastructure and Bautista’s resettlement plan, at least 6,584 families who have built their lives on UP land continue to assert their position: they want to stay.

The OCR assured, however, that construction of the remaining phases will not begin until the residents of Village C, numbering up to 133 families, are resettled.

“We will eventually reclaim the land in Village C, but since there are still no housing plans and resettlements for the residents, our hands are tied,” said Community Relations Officer Camille Nadua.

The fight for basic human rights

As households in Village C continue to be displaced, residents all over remain in constant fear of forced demolition. In the meantime, they ask for access to basic facilities which would improve quality of life in the SBU areas.

Remigio Lucas in one such resident. Currently residing at C.P. Garcia, Lucas asks for the repeal of the OVCCA Memo No. 14-50, which prohibits residents of Village C and Pook Arboretum to apply for Road Right-of-Way, or the access to electricity and water connections. This as a result of the existence of planned projects for the area.

“It’s because they (OCR) adhere to the mindset that the communities will be relocated soon, that they are stripped of their rights to electricity and water because of the cost. I don’t think that’s right at all,” Lucas said.

Omay added that in her 20 years living in UP Diliman, not one attempt was made by the administration to build a functional road for Pook Malinis. Instead, they’ve made do with a dirt road which remains perennially muddy because of the lack of an operational sewage system in the community.

All of which run against the ideals set in the UP Master Development Plan, the key architectural agenda of the university, which states that all ISFs “shall be treated with sensitivity, compassion and social justice.”

“We will eventually reclaim the land in Village C, but since there are still no housing plans and resettlements for the residents, our hands are tied.”

The failure of the Saloma containment policy, and the continued stalling between the university and local government have delayed relocation efforts which could’ve started a decade ago. Meanwhile, residents from all 14 SBU areas remain in constant vigilance, and in constant fear, stripped of access to their basic human rights.

This article first appeared in KRISIS (Issue 1, AY 2016-2017) – Self-Built Unit (SBU) Edition on March 17, 2017.